**Contains major plot spoilers for The Mysterious Affair at Styles and minor plot spoilers for Bleak House by Charles Dickens and The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins.**

See the previous post, Dressed to the Strychnines: Act I, for a summary of the creation of Agatha Christie’s first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, as well as a synopsis of the book. The post you are reading will provide an in-depth description of strychnine poisoning in the context of Christie’s first novel.

The Herb of Death

The description of the agonizing death of Emily Inglethorp concludes:

A final convulsion lifted her head from the bed, until she appeared to rest upon her head and her heels, with her body arched in an extraordinary way.

This characteristic effect immediately led doctors (probably including Lawrence Cavendish, though he was loathe to admit) to suspect strychnine poisoning caused Mrs. Inglethorp’s death. Strychnine would appear in five of Agatha Christie’s novels and five short stories altogether, dispatching a total of five characters.

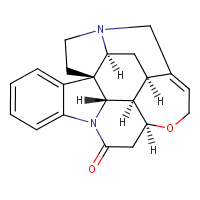

Strychnine is derived from plants in the genus Strychnos, and the compound is an alkaloid without any odor but with a very bitter taste. Its crystals are long, thin, and colorless, and they are poorly soluble in water. It takes nearly 7 liters of water to dissolve 1 gram, but as a salt its solubility is improved without impacting toxicity. Historically, the poison was used as a pesticide or to raise blood pressure but was not used medically at the time Styles was written.

Absorption and Metabolism

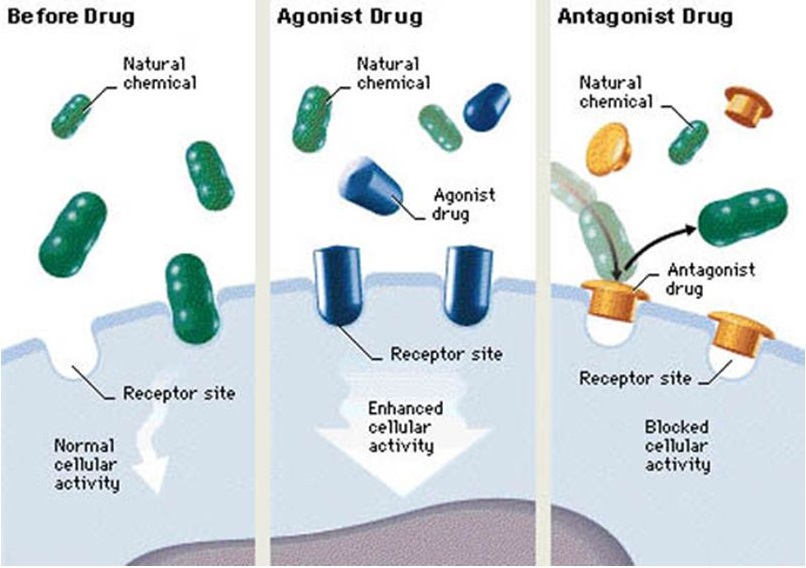

In the human body, strychnine is absorbed across the small intestine following ingestion. Its toxic effects are due to its propensity to bind to glycine receptors in the central nervous system (CNS), which prevents the typical intercellular communication in which glycine participates. In between neurons, the functional cells of the CNS, are small gulfs referred to as synapses, which allow for the transfer of chemical messages (neurotransmitters). Chemicals released from the tail end (axon) of one neuron travel across the synapse to interact with a second, downstream neuron through specific receptors. One of these neurotransmitters, glycine, counteracts the effects of acetylcholine, the neurotransmitter released when muscle cells are activated. Glycine acts like a mute on a trumpet; much greater activation of the upstream neurons by acetylcholine would be needed to stimulate muscle contraction in the presence of glycine.

Strychnine has a greater affinity than naturally produced glycine for the glycine receptor; it is 300% more energetically favorable for strychnine to bind with the glycine receptor compared with a similar amount of glycine. When strychnine replaces glycine, the muted trumpet referenced above loses its mute and will respond at full strength to the slightest stimulus. In this case, strychnine is an antagonist of the glycine receptor; it binds to the receptor instead of glycine but induces no response in the cell. (An agonist is a chemical that would bind instead of the typical chemical that binds to the receptor and induces the typical response.) Consequently, strychnine poisoning causes an uncontrolled sustaining of muscle contraction.

Deadly Effects

In humans the muscles on the back of the body (dorsal side) tend to be stronger than on the front of the body (ventral side), so strychnine’s ability to prevent the inhibition of muscle contraction results in a violent arching of the back, as described for Emily Inglethorp. Other muscle spasming patterns may be observed, depending on the location of neurons affected by strychnine. Because strychnine affects motor neurons, other cells in the CNS would function normally after poisoning, and the victim would be completely conscious and aware during the muscle spasming.

Within 15 to 30 minutes after exposure to strychnine (typically through ingestion via food or drink), the poisoning symptoms begin to manifest as muscle tingling and twitching, which is quickly followed by nausea and vomiting. The muscle twitching intensifies into violent muscle spasms interrupted by short periods of relaxation. The direct cause of death is often asphyxiation; the violent contraction of the muscles in the chest surrounding the respiratory system suffocates the unfortunate soul.

There is no specific antidote for strychnine, but if administered quickly enough, muscle relaxers and anticonvulsant drugs may stave off death. Modern treatment would consist of diazepam (Valium) and artificial respiration to maintain breathing while minimizing muscle contractions. Activated charcoal may also be administered by mouth to prevent further absorption through the gastrointestinal tract. In A is for Arsenic: The Poisons of Agatha Christie, author Kathryn Harkup recounts a presentation at the French Academy of Medicine in 1831, where pharmacist P. F. Touery swallowed 10 times the lethal dose of strychnine mixed with charcoal. He subsequently developed no symptoms of strychnine poisoning.

Partners in Crime

Another confounding factor in The Mysterious Affair at Styles is the administration of a so-called “narcotic” to Mrs. Inglethorp by Mary Cavendish. Christie never reveals which specific narcotic was added to Mrs. Inglethorp’s cocoa, but it may very well be morphine as it was given to induce sleep.

Worth noting in this discussion of Styles is the fact that a common side effect of morphine is constipation, which results from diminishing muscle contractions along the gastrointestinal tract. This decrease in smooth muscle contractions may delay the transit of foodstuffs from the stomach into the small intestine by up to 12 hours. Since strychnine is absorbed in the small intestine rather than the stomach, a delay in absorption caused by the morphine in her cocoa would have delayed Mrs. Inglethorp’s symptoms of strychnine poisoning.

The inventor of morphine, Dr. Friedrich Sertuerner, gave it the name morphium after Morpheus, the Greek god of sleep. Morphine is an opioid and is typically used as an analgesic. It is highly addictive and exerts the same effects as heroin in the body. Because heroin and morphine feature more prominently in other Christie stories, greater detail of their physiological effects will be discussed in future posts.

Potassium bromide was used so frequently as a sedative at the turn of the century that the term “bromide” became synonymous with a dull person or a boring platitude.

Of course, the ingenious and almost undetected administration of strychnine by the perpetrators was accomplished by simply manipulating the tonics that Mrs. Inglethorp already took on a regular basis. She was in the habit of taking potassium bromide powders as a sedative and also took a tonic that contained strychnine every night. In the 1920s, tonics containing small quantities of strychnine were sold over the counter and purported to have stimulative effects, increasing alertness and activity; however, there is no evidence that strychnine acts as a stimulant. The whole bottle of Mrs. Inglethorp’s tonic would contain a lethal dose of strychnine, but she only took a small amount every night with no ill effects. The metabolic half-life within the human body is about 10 hours, meaning that the concentration of strychnine present in the body at a specific time will be decreased by 50% when measured at 10 hours afterwards, so there would be no additive effects taking small doses every 24 hours for a typical adult.

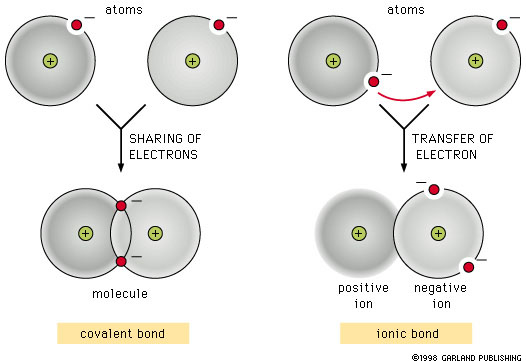

As mentioned previously, strychnine is poorly soluble in water and is consequently used in a salt form, such as strychnine sulfate. Unlike other molecular compounds, the “bonds” that hold together a salt are ionic charges, rather than shared electrons. In general, molecules will be prone to form compounds that are in the lowest energy state possible. In a solution in which a strychnine salt is dissolved in water, the addition of another salt (such as potassium bromide) would cause the dissociation of strychnine from its ionic counterpart to form an insoluble precipitate that would settle at the bottom of the bottle. It was a simple matter for Evelyn Howard to add one or two of Mrs. Inglethorp’s bromide powders to her strychnine tonic and wait for the unsuspecting victim to take the final draught with a concentrated and lethal dose of strychnine.

By chance, this final dose was taken on the same night that Mary Cavendish chose to also poison Mrs. Inglethorp with a narcotic, although her motive was not to kill. The addition of this third chemical compound proved to be a red herring but delayed the effect of the strychnine to confuse the method of murder. The overall scheme to murder Mrs. Inglethorp with her own “medicine” did involve some scientific understanding, which is explained by the fact that Evelyn Howard’s father was a doctor and she herself seems to be a nurse. During the denouement, Poirot reads from The Art of Dispensing: A Treatise on the Methods and Processes involved in Compounding Medical Prescriptions, which he states could be found at the hospital dispensary. This is indeed an important book in the history of pharmacology and was first published in 1888.

A Stylish Success

The Mysterious Affair at Styles was overall well reviewed, but Agatha’s favorite review was from The Pharmaceutic Journal, a scientific journal who praised the accuracy of the chemistry in the story. The novel is almost a love letter to chemistry, and it is easy to imagine Christie wiling away the hours in her dispensary imaging the plot. It also marks a welcome progression for the detective novel back in to the scientific method.

The development of the mystery novel at this point in history was brief but had not been marked by great scientific integrity. The introduction of Inspector Bucket’s deductive powers into Bleak House by Charles Dickens were somewhat diminished by the inclusion of spontaneous combustion as a key plot point, and the use of an opium “experiment” in the conclusion of The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins also left something to be desired with regards to what Poirot calls “order and method.” The introduction of Sherlock Holmes a few years later by physician and author Arthur Conan Doyle was attended by a “profound knowledge of chemistry” by Holmes, according to his biographer, Dr. John Watson. Further in the canon, Holmes’s deference to science is somewhat hindered by his creator’s burgeoning interest in spirituality. Nevertheless, there was an opening for detective novels with accurate and intriguing science that was readily assumed by Christie.

Meanwhile in True Crime...

At one point in history, strychnine was reported to be the third most frequently used poison employed by murderers, behind arsenic and cyanide. No longer often reported as a cause of death, strychnine poisoning was involved in two noteworthy criminal cases around the time of the publication of Styles. As noted in the novel, strychnine is extremely bitter and difficult to conceal in food and drink. The poison can be detected in water in as low as 1 part in 70,000; a fatal dose would need to be diluted in 7 liters of water, rendering this method difficult to execute without raising suspicion.

In 1924, just a few years after the release of the novel, Mrs. Mabel Jones, the wife of a British innkeeper, was convalescing from an unspecified illness in France. There she met a wireless (telegraph) operator named Jean-Pierre Vaquier, and the two began an affair. Somewhat romantically, as neither spoke the other’s language, Mabel brought a French/English dictionary along on their assignations to use to communicate. A short time after Mabel returned to England, Jean-Pierre followed and eventually lodged in the hotel run by Mabel’s husband, Mr. Alfred Jones, the Blue Anchor Hotel in Byfleet, Surrey. Mabel and Jean-Pierre continued the affair in England.

Alfred Jones took regular doses of bromide powders to counteract the effects of alcohol, which he was prone to abuse. Alfred’s bromide was kept in a small blue bottle stored in the hotel bar. One morning, Alfred noted upon preparing a dose of his bromide that the powders were not as fizzy as he was accustomed to seeing them, and when Mabel observed the bottle, there were long crystals mixed in with the usual fine powder. She tasted the long crystals, which were bitter, and then gave her husband some salt water as an emetic (to stimulate vomiting) and some tea with soda (to calm the stomach). Despite his wife’s best efforts, Alfred succumbed to the convulsions and died about 90 minutes after taking the tainted bromide.

Jean-Pierre immediately came under suspicion. Investigators seized the blue bottle, which still contained traces of strychnine despite being cleaned. Evidence emerged that Jean-Pierre had purchased strychnine for the stated purpose of “wireless experiments” and signed the poison register with a false name. During his criminal trial, an independent wireless expert testified that there were no known applications of strychnine in wireless communications. Jean-Pierre was found guilty and hanged for the murder of his lover’s husband; the ghost of Alfred Jones is said to haunt the Blue Anchor Hotel to this day.

Another case of murder involving strychnine from several years prior to the publication of Styles was Dr. Thomas Neill Cream (The Lambeth Poisoner), who murdered four women in 1892. As a young doctor in Canada, Dr. Cream had a practice in which he regularly performed abortions until the dead body of a young chambermaid was found in his office, and he fled to Chicago.

After resuming his work as a physician in the United States, another young woman associated with Dr. Cream died. He was arrested under suspicion for her murder but was ultimately not charged. Dr. Cream was found guilty of murder the following year after he poisoned the husband of one of his patients with strychnine. Although given a life sentence, Dr. Cream was released 10 years later due to “good behavior.” Dr. Cream traveled to England upon his release.

Soon after arriving in London, Dr. Cream began poisoning sex workers by administering pills that he stated would improve the women’s complexions. The pills, however, were composed primarily of strychnine, and the consumers would perish in agony several hours later. In short order, Dr. Cream was arrested and rapidly convicted, then hanged at Newgate Prison. A perhaps apocryphal story asserts that his last words were “I am Jack the…,” with the hangman’s noose pulling taut prior to completion of the sentence. Dr. Cream was imprisoned in the US in 1888, during Jack the Ripper’s murderous spree in Whitechapel, so it is not likely that he was the perpetrator.