**Contains major plot spoilers for Ingots of Gold, The Thumb Mark of St. Peter, and The Blue Geranium and minor plot spoilers for The Companion and The Big Four.**

An Acidulated Spinster

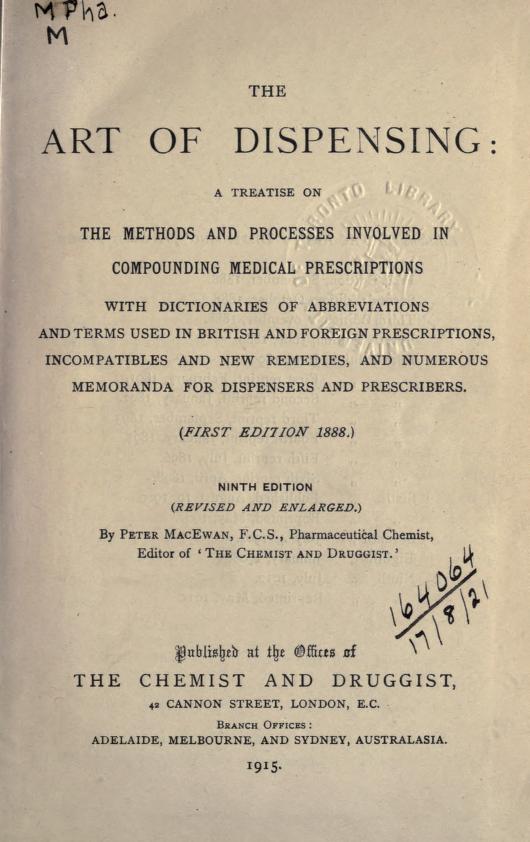

Although the first full-length novel with Miss Jane Marple as the detective was published in 1930 (Murder at the Vicarage), the character initially appeared in print in a series of 6 short stories Christie wrote for a magazine in 1928. In 1932, an additional 6 stories were added, and the compilation was published as The Thirteen Problems (UK) or The Tuesday Club Murders (US).

In her Autobiography, Christie reflects,

The original title was Thirteen at Dinner, which was used the following year for a different Christie novel featuring Hercule Poirot and alternatively titled Lord Edgware Dies.

Murder at the Vicarage was published in 1930, but I cannot remember where, when or how I wrote it, why I came to write it, or even what suggested to me that I should select a new character—Miss Marple—to act as the sleuth in the story. Certainly at the time I had no intention of continuing her for the rest of my life. I did not know that she was to become a rival to Hercule Poirot.

She continues,

I think it is possible that Miss Marple arose from the pleasure I had taken in portraying Dr. Sheppard’s sister in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. She had been my favourite character in the book—an acidulated spinster, full of curiosity, knowing everything, hearing everything: the complete detective service in the home.

A Rag-Tag Group

The Thirteen Problems is a collection of short stories, as told by a group of companions gathered in the fictional village of St. Mary Mead. In addition to Miss Marple, the members of the “Tuesday Night Club” include Raymond West, Marple’s nephew and a novelist; Joyce Lempriere, a painter who is romantically involved with Raymond; Mr. Pettigrew, a local solicitor; Henry Clithering, former commissioner of Scotland Yard; and Dr. Pender, an elderly clergyman. With the addition of the last 6 stories, the characters of Major and Dolly Bantry were added, and they would be featured in subsequent Marple novels.

The stories recounted by the companions are tales of poisoning, mysterious rituals, theft, murder, blank wills, and espionage — all Christie mainstays. In each of the stories, Miss Marple surprises the others by arriving at the solutions to the mysteries by drawing parallels to her observations of life in St. Mary Mead. In Ingots of Gold, Miss Marple points out that one of the offenders was pretending to be a gardener, which is obvious to her as gardeners do not work on Whit Monday, and in The Companion, Miss Marple recalls the story of a Mrs. Trout, “only a person–not a very nice person–in the village”:

I must confess it does remind me, just a little, of old Mrs. Trout. She drew the old age pension, you know, for three old women who were dead, in different parishes… It’s just Mrs. Trout over again. Mrs. Trout was very good at red herrings, but she met her match in me.

This blog post will focus on two stories within the collection: The Thumb Mark of St. Peter and The Blue Geranium. Both stories involve poisoning and have been mimicked or reproduced in some interesting true crime cases.

St. Peter's Thumb

The Thumb Mark of St. Peter marks Miss Marple’s contribution of a mystery story to the Tuesday Night Club. She recounts a story involving her niece, Mabel, whose husband Geoffrey suddenly dies. Rumors circulate that Mabel has poisoned her husband, whom a doctor concludes to have died from eating poisoned mushrooms. Mabel reveals that she had bought arsenic at the chemist’s the morning of her husband’s death with the intention of poisoning herself. The household staff report that in the evening, Geoffrey was in great agony and unable to swallow; he could only speak in a garbled voice, and he rambled about “a heap of fish”.

Through the persistence of Miss Marple in her investigation, the husband’s body is exhumed and tested for poisoning, but “there was nothing to show by what means [the] deceased had come to his death.” Miss Marple speaks with the pathologist, who concedes that the death may have been caused by a strong vegetable alkaloid. Deep in contemplation, she stumbles upon a fish monger’s shop, which draws her mind back to the “heap of fish”. She reinterviews the cook, who states that Geoffrey had said “pile” rather than “heap” and referred to a specific fish beginning with the letter “C”. Miss Marple consults an index of drugs and discovers the compound pilocarpine, which could be easily misconstrued as a “pile of carp” or “heap of fish”.

Given the use of pilocarpine as an antidote to atropine poisoning, Miss Marple ascertains that the husband’s elderly father had actually committed the murder by emptying his bottle of eye drops (containing atropine sulfate) into his son’s water glass. When confronted, the old man confesses his crime, which he did to prevent Geoffrey from institutionalizing him. At the conclusion of her story, Sir Henry Clithering tells Miss Marple, “I shall recommend Scotland Yard to come to you for advice.”

To Cut the Thread of Life

Atropine is a plant alkaloid derived from Atropa belladonna, or deadly nightshade, and is named after Atropis, one of the three fates in Greek mythology whose role was to cut the thread of life. The name “belladonna” (meaning “beautiful lady” in Italian) originates from the use of the juice of the berries by women to dilate their pupils in order to enhance their attractiveness. Although excessive use can cause blurred vision and blindness, this function of atropine is still used in ophthalmology to this day to allow for eye examinations and relieve pressure buildup.

In The Big Four, Hercule Poitrot uses belladonna in his eyes to disguise himself as his “brother”, Achille Poirot, an invention to elude defeat by the novel’s villains.

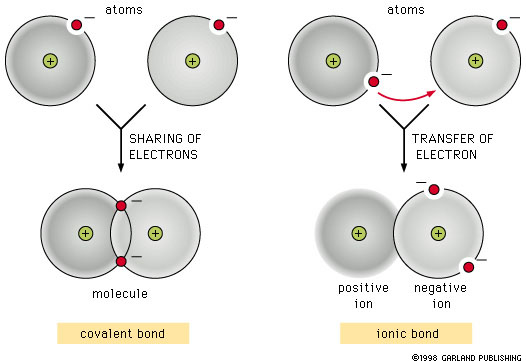

Due to its chemical structure, atropine is not highly water soluble; therefore, a salt form is generally used in medications, such as the atropine sulfate found in the elderly father’s eyedrops in The Thumb Mark of St. Peter. As discussed in Dressed to the Strychnines, Act II, salts are formed by the ionic pairing of compounds rather than the sharing of electrons in covalent bonds. Consequently, there is no change to the action of atropine in its salt form, rather it is more easily absorbed across mucous membranes and the gastrointestinal tract.

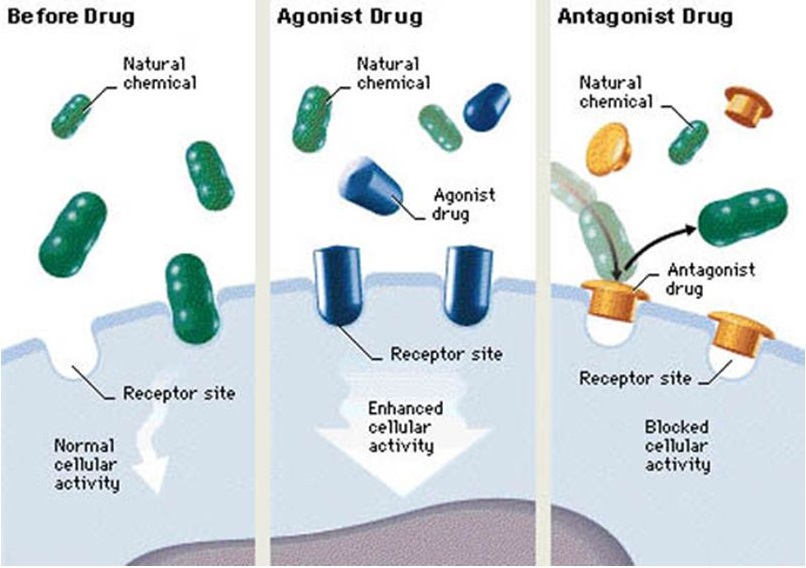

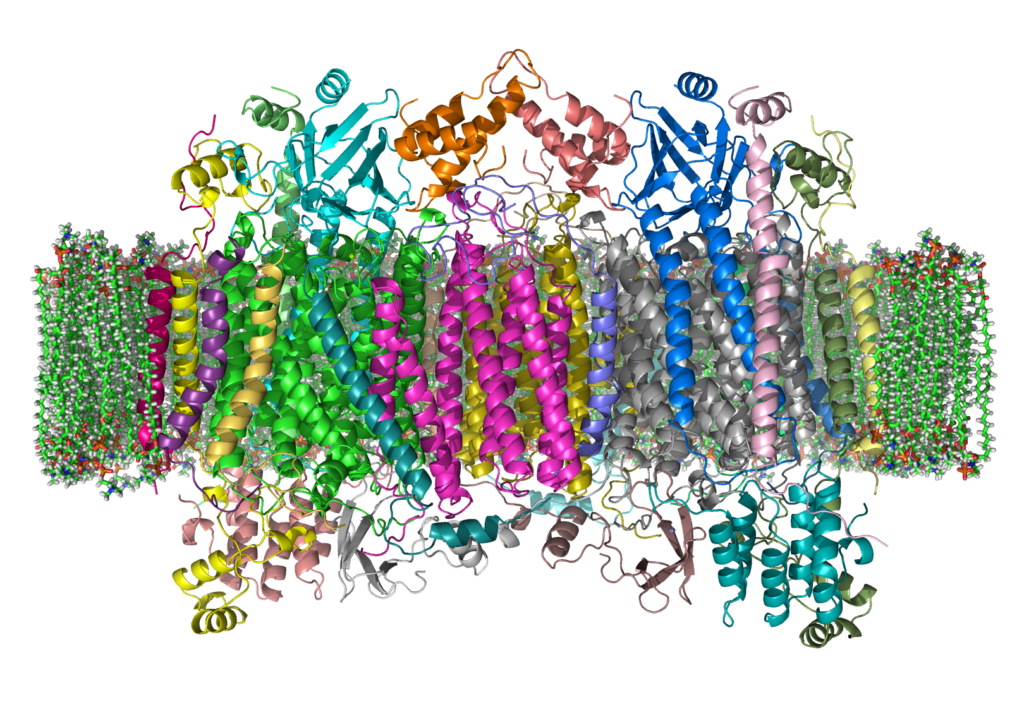

Once in the bloodstream–and similar to strychnine–atropine acts as an antagonist to the neurotransmitter receptors of acetylcholine, which are also called muscarinic receptors. Acetylcholine is the primary neurotransmitter of the parasympathetic nervous system, and its signaling modulates the production of bodily fluids such as mucus in the upper gastrointestinal tract, lungs, heart, and sweat glands. When atropine antagonizes the muscarinic receptors, the production of fluids diminishes; another medicinal use of atropine sulfate is to decrease mucous secretions in the bronchioles of the lungs prior to surgeries to prevent any blocking of the airway.

The use of atropine sulfate in eyedrops may treat a condition called miosis, which is excessive constriction of the pupils, or anterior uveitis, which is inflammation of the uvea or iris. Christie does not note the specific ophthalmologic malady suffered by the father in The Thumb Mark of St. Peter, but by distilling atropine in the eye, the muscles that control the iris are paralyzed, dilating the pupil and relieving the build-up of pressure. By keeping the dose administered low, the effect of blurred vision is temporary, though the dilation of the pupils may persist for several days.

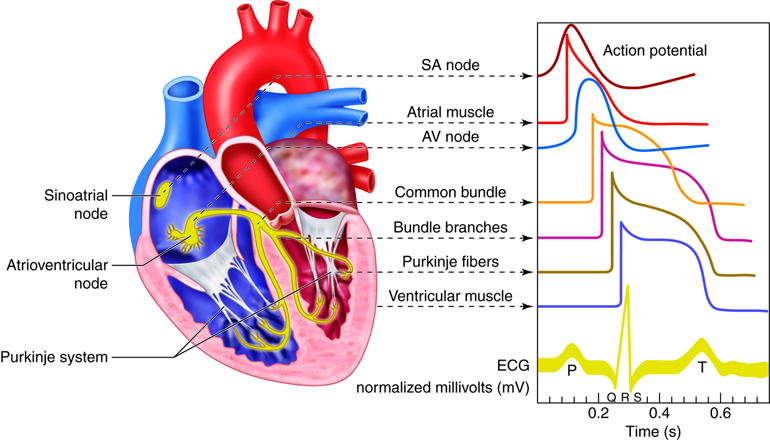

When atropine is ingested in large amounts (approximately 10 to 100mg, depending on the form), its effects are lethal because it quickly inhibits the signaling of the parasympathetic nervous system to the heart. Typically, acetylcholine released by the parasympathetic nervous system via signaling through the vagus nerve acts on the sinoatrial node of the heart, which controls the heart rate. In the presence of acetylcholine, the heart rate is slowed to less than 100bpm. When acted upon by the antagonist atropine, the heart no longer receives the signals to slow its rate of beating. This increase in heart rate leads to an increase in respiratory rate, coupled with a decrease in fluid secretions. The condition is accompanied by hallucinations, muscle convulsions, and coma, and can lead to death.

The poison scopolamine has similar effects as atropine and was the poison allegedly used by Dr. Hawley Crippen to dispatch his wife in a well-known historical true crime. Christie also included scopolamine as a murder weapon in her first play, Black Coffee.

A Pile of Carp

Like atropine, pilocarpine is a plant alkaloid, and it is derived from the leaves of Pilocarpus pinnatifolius. It acts in direct opposition to atropine, as it is an agonist of the same receptors. When it binds to acetylcholine receptors, it exerts the same effect as the neurotransmitter, increasing mucous secretion and slowing the heartbeat. Coincidentally, pilocarpine is also used medically in the form of eyedrops to treat glaucoma.

Because of their opposing actions, either pilocarpine or atropine can be used as an antidote to poisoning with the other compound. As in The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Christie uses her specialized knowledge from her time in the dispensary to create a clever poisoning mystery.

Meanwhile in True Crime...

In what may be the true crime case that was most directly inspired by a work of Christie’s, an elderly French couple was killed by their nephew, who had added atropine from a bottle of eyedrops to a bottle of wine he gave the couple. The nephew, Roland Roussel, knew his aunt and uncle did not typically consume alcohol and assumed that they would share the wine with a woman who often visited and whom he blamed for the death of his mother. Unfortunately, the aunt and uncle decided to drink the bottle of wine on Christmas Day. The uncle died, and the aunt was comatose.

A neighbor discovered the couple, and doctors first speculated that food-borne illness was to blame. A few days later, the couple’s son-in-law and a carpenter went to the house to place the uncle’s body in a coffin. As there was still wine remaining in the bottle, both men drank a small amount and were rendered unconscious. They received proper medical treatment, and the wine was tested for contaminants, revealing the addition of atropine to the bottle. With this major clue, investigators directed their attention to Roland Roussel. Upon searching his apartment, they discovered a copy of The Thirteen Problems with certain passages in The Thumb Mark of St. Peter underlined. No further information about the fate of Roussel has been published.

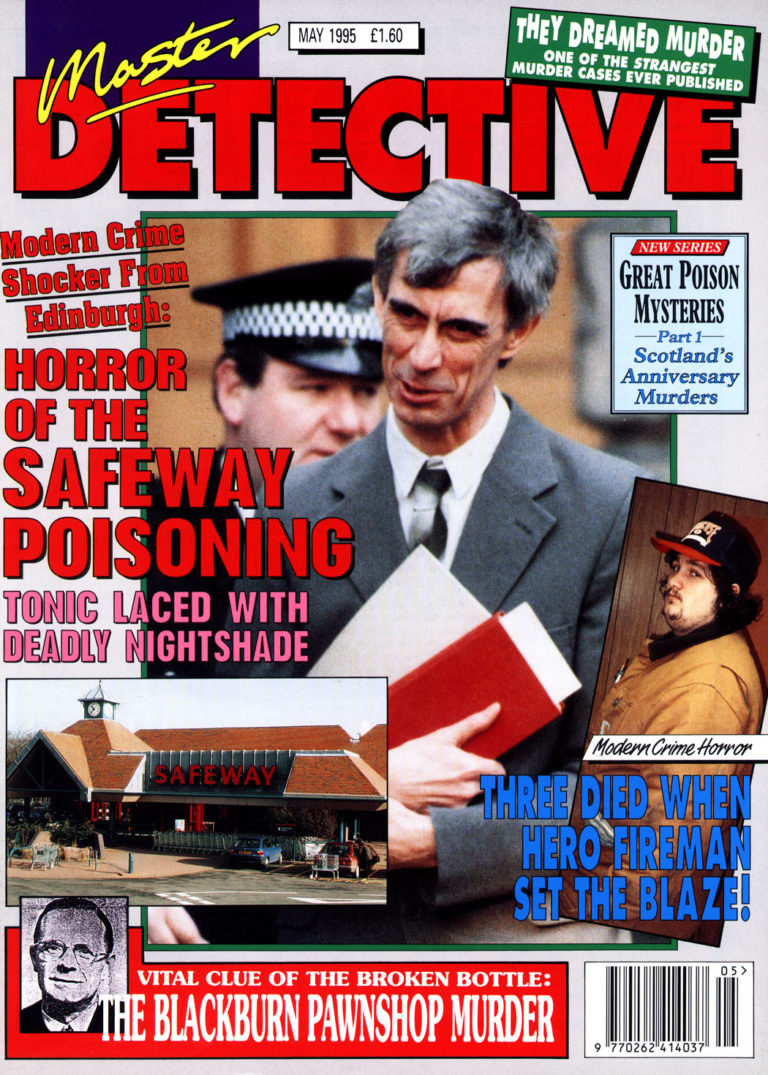

In a case of attempted murder, Paul Agutter, a biology lecturer at Edinburgh University, added atropine to a bottle of tonic water that he used to make his wife a gin and tonic. She complained of the bitter taste and only drank a small amount, but she ingested enough of the poison to become seriously ill. So elaborate was the husband’s plan that he added atropine to multiple bottles of tonic water and returned them to the shelf of a local supermarket. Although each of these bottles had smaller quantities than the bottle used for Mrs. Agutter’s drink, 8 people were hospitalized after consuming tonic water purchased from the supermarket.

Closed-circuit television in the market captured Agutter placing the bottles on the shelf, and an employee also observed him doing so. Agutter’s attempt to manipulate the authorities into suspecting that a lunatic was poisoning bottles of tonic water and that his wife just happened to be a victim was not successful; he served 7 years in prison for attempted murder. The wife recovered.

Blue Flowers

Another story in The Thirteen Problems also involves poisoning; however, the toxin in this instance is cyanide. In The Blue Geranium, Dolly Bantry shares what she considers a supernatural tale with Miss Marple and some other members of the Tuesday Night Club. The tale centers around the wife of family friend George Pritchard, who is never given a Christian name. Mrs. Pritchard is a difficult, demanding woman, with an unspecified medical condition that renders her somewhat disabled. A series of nurses live with the couple to care for Mrs. Pritchard, but each is dismissed after a short time.

Mrs. Pritchard is also partial to spiritual mediums. One of the more competent nurses, Nurse Copling, arranges for a visit from Zarida, Psychic Reader of the Future. Following the visit, Mrs. Pritchard is distraught, smelling frequently from her bottle of smelling salts. She reports that Zarida says there is evil and danger present in the house. More specifically, the psychic tells Mrs. Pritchard, “Blue flowers are fatal to you–remember that.” Two days later, Mrs. Pritchard receives a letter from Zarida that states,

I have seen the future. Be warned before it is too late. Beware of the Full Moon. The Blue Primrose means Warning; the Blue Hollyhock means Danger; the Blue Geranium means Death…

The morning after the next Full Moon, which is a few days later, Mrs. Pritchard rings her bell violently to report that one of the pink primroses illustrated on her wallpaper had turned blue. Before the next Full Moon, Mrs. Pritchard has her husband and nurse both study the wallpaper and lock the door to her room. The next morning, one of the hollyhocks on the wallpaper has turned blue. Although Nurse Copling is alarmed and asks George to move Mrs. Pritchard from the house, he retorts, “If all the flowers on that damned wall turned into blue devils it couldn’t kill anyone!”

The morning after the following Full Moon, there is no bell ringing heard from Mrs. Pritchard’s room. George chisels the door open to discover Mrs. Pritchard’s lifeless body in bed. She has dropped her bottle of smelling salts on the bed, and one of the pink geraniums on the wallpaper has turned blue. There is a slight smell of gas in her room but not enough to have led to death. Although there is suspicion that George murdered his wife, there is no indication following her autopsy that there was any foul play. It is generally accepted that the woman died of fright.

Of course, Miss Marple does not accept this explanation. She states,

Well, if I did [wish to kill someone], I shouldn’t be at all satisfied to trust to fright. I know one reads of people dying of it, but it seems a very uncertain sort of thing, and the most nervous people are far more brave than one really thinks they are. I should like something definite and certain, and make a thoroughly good plan about it.

The reassurance that pink flowers had turned blue (rather than yellow flowers) further cements her idea. She reveals that the culprit is Nurse Copling, and the changing colors of the flowers on the wallpaper was accomplished through the use of litmus paper, which nurses often carry.

Litmus paper contains the molecule 7-hydroxyphenoxazone, a weak acid which changes to a blue color at an alkaline (basic) pH of 8.3 or higher. When a strong base is added, the molecule donates a hydrogen atom, and the resulting conjugate base has a blue color.

Miss Marple reveals that Nurse Copling has replaced Mrs. Pritchard’s smelling salts with potassium cyanide, which is visually indistinguishable. Confident that Mrs. Pritchard would smell at them when faced with the blue flowers, Nurse Copling stages the visit from Zarida and a follow-up letter to distress the poor woman. The strong ammonia fumes from the smelling salts, which are basic or alkaline, would cause the litmus paper that Nurse Copling had pasted on top of the flower wallpaper to turn blue. While George Pritchard calls for a doctor, the nurse quickly substitutes the cyanide bottle with standard smelling salts and turns on the gas a small amount to hide the scent of bitter almonds typical of cyanide. Miss Marple speculates that Nurse Copling has fallen in love with George Pritchard, although he does not return her affections.

Because cyanide is prevalent throughout Christie’s work, an in-depth discussion of this poison will be reserved for a future post. Briefly, cyanide is rapidly converted into hydrogen cyanide in the gastrointestinal tract, and this form is readily absorbed into the bloodstream. Cyanide displaces oxygen in hemoglobin molecules, which serve to transport oxygen from the lungs throughout the body. With this method of transportation, cyanide can be delivered to cells in various body systems.

Once in the cell, cyanide binds to the enzyme cytochrome c oxidase; this enzyme catalyzes the final step of oxidative phosphorylation (or aerobic metabolism) in the mitochondria. Cyanide is an antagonist to cytochrome c oxidase; after it binds, the chemical reactions responsible for generating cellular energy stop, resulting in cell death. Cyanide can kill within minutes to hours due to this widespread cell death.

The Auburn Cyanide Murders of 1986

Although this author was unable to locate any true crime cases that involved the substitution of smelling salts with potassium cyanide, there are several cases where cyanide has been added to otherwise safe medications. Following the Chicago Tylenol cyanide poisonings in 1982, Bruce Nickell and Susan Snow were killed by Excedrin capsules poisoned with cyanide in Washington state.

Although Bruce’s death was first, it was not until after Susan died that his death was attributed to cyanide poisoning. Susan was 40 years old and suffered from headaches but was otherwise healthy. On the morning of 11 Jun 1986, Susan took two capsules of Extra-Strength Excedrin and was discovered collapsed in the bathroom a short time later by her daughter. She was clinging to life but died a short time later at the hospital.

During Susan’s autopsy, the Assistant Medical Examiner smelled the distinctive bitter almond smell that accompanies cyanide. A blood test confirmed that Susan had died from acute cyanide poisoning. Investigators were baffled as to the source, until Susan’s twin sister reached for some Excedrin on the day of Susan’s funeral. She noted to investigators that Susan usually purchased Excedrin tablets, and it was unusual for her to have Excedrin gel capsules. Tests of the remaining capsules in Susan’s bottle of Excedrin showed that three more capsules contained lethal quantities of cyanide.

The ability to smell cyanide is a genetic trait, which has been shown to be prevalent in approximately 50% of people.

The testing of Excedrin for cyanide expanded to include other bottles from the same lot number as Susan’s. An additional tainted bottle was discovered at a supermarket in Kent, Washington, and Bristol-Myers, the manufacturer of Excedrin, issued a recall for all bottles of Extra-Strength Excedrin in the Seattle, Washington area. Several pharmaceutical companies banded together to offer a $300,000 reward for the apprehension of the person responsible for poisoning the capsules.

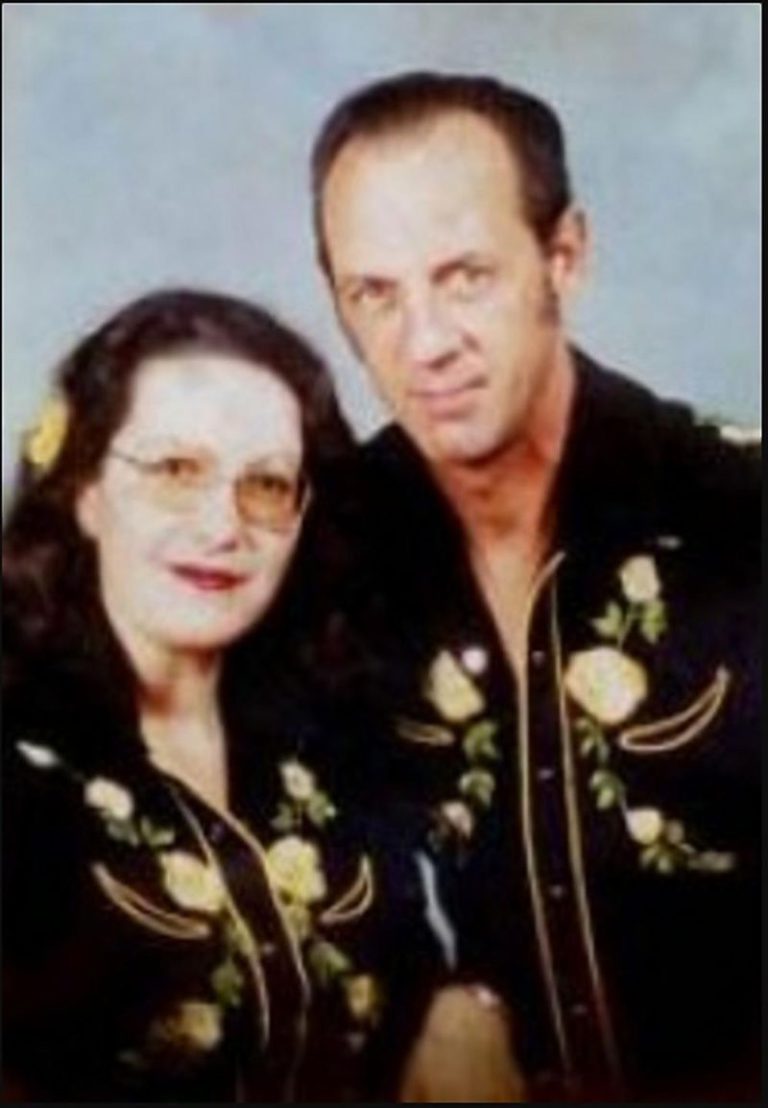

Once this information about the tainted Excedrin was publicized, 42-year-old Stella Nickell phoned authorities, stating that her husband Bruce had recently died after taking four Excedrin capsules from a bottle with the same lot number that was the target of the recall. Bruce was 52 years old and a heavy smoker, and doctors had concluded he died from complications related to emphysema. With the new information from Susan Snow’s death, investigators tested Bruce’s body for traces of cyanide, which were indeed present.

Bristol-Myers responded by recalling all bottles of Excedrin capsules in the United States, quickly followed by a recall of all of the company’s nonprescription capsule medications. A few days later, investigators discovered a cyanide-tainted bottle of Anacin-3, an Excedrin competitor, and Washington state issued a 90-day ban on the sale of all nonprescription capsule medications.

The contaminated medications were sent to the FBI Crime Lab in Washington, D.C., for examination. The cyanide salt that had been added to the medications contained small granules of a green substance. Additional testing showed that the green substance was the commercial product Algae Destroyer, which is used to clean home aquariums. Investigators surmised that the culprit must have used a container to crush or mix the cyanide that had been previously used to crush Algae Destroyer tablets.

Around the same time, investigators were focusing on Stella Nickell. In addition to owning several tropical fish aquariums, the widow had inherited a total of $175,000 from Bruce’s multiple life insurance policies. Document examiners at the FBI had determined that Bruce’s signature had been forged on the applications, and Stella inherited an additional $100,000 now that her husband’s death was determined to have been accidental. Furthermore, Stella had two tainted Excedrin bottles out of the total of five that had surfaced throughout the country, and she initially refused to undergo a polygraph examination, which she subsequently failed.

The clues continued to accumulate. Stella’s 27-year-old daughter Cindy approached authorities, recalling that her mother told her several times that she wanted to kill Bruce as she had become bored in the relationship. She admitted to trying to kill him with foxglove, after which he was sick for a few days and then recovered. Cindy also stated her mother had researched poisons at the library.

Foxglove is a source of the poison digitalis, which Christie used in several novels and stories including Appointment with Death, Postern of Fate, and The Herb of Death in The Thirteen Problems.

Records from the Auburn Public Library were subpoenaed, and the FBI detected Stella Nickell’s fingerprints on pages related to cyanide in books such as Deadly Harvest. This evidence, along with Stella’s financial gain, Cindy’s testimony, and the manager of a tropical fish store positively identifying Stella as a purchaser of Algae Destroyer, led investigators to arrest Stella for the double murder in December 1987.

Stella was charged with product tampering that resulted in the deaths of Bruce Nickell and Susan Snow under the 1983 Federal Anti-Tampering Law, which was a result of the Chicago Tylenol cyanide poisonings. Jurors found her guilty, and she received two life sentences. Her current release date is 10 Jul 2040, when she will be 97 years old.