Agatha Christie (1890-1976): Polymath and Natural Scientist

Agatha Christie was born in September 1890 and lived through 1976, so her work was inspired by and utilized the concepts of forensic science that were established during this time period.

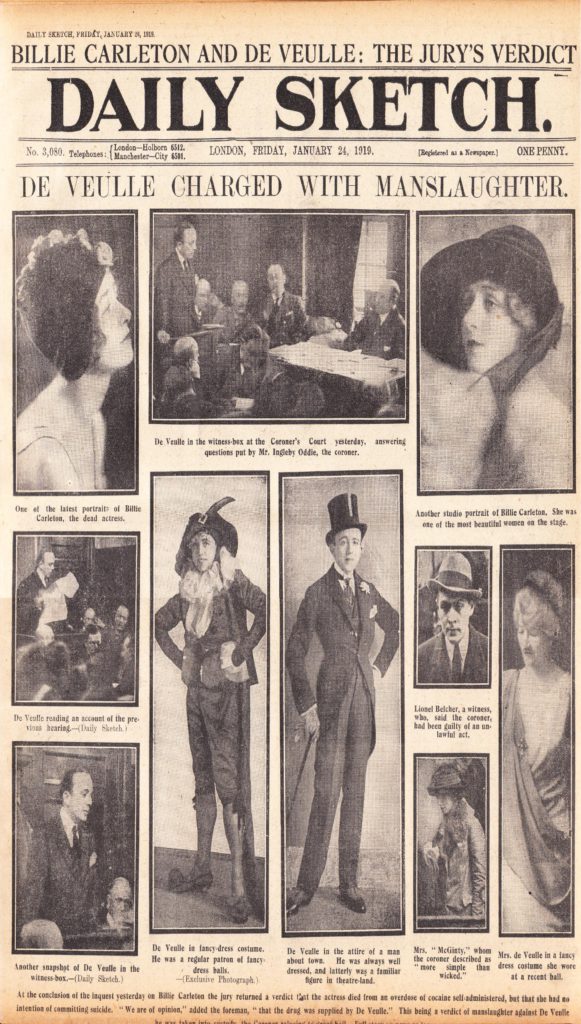

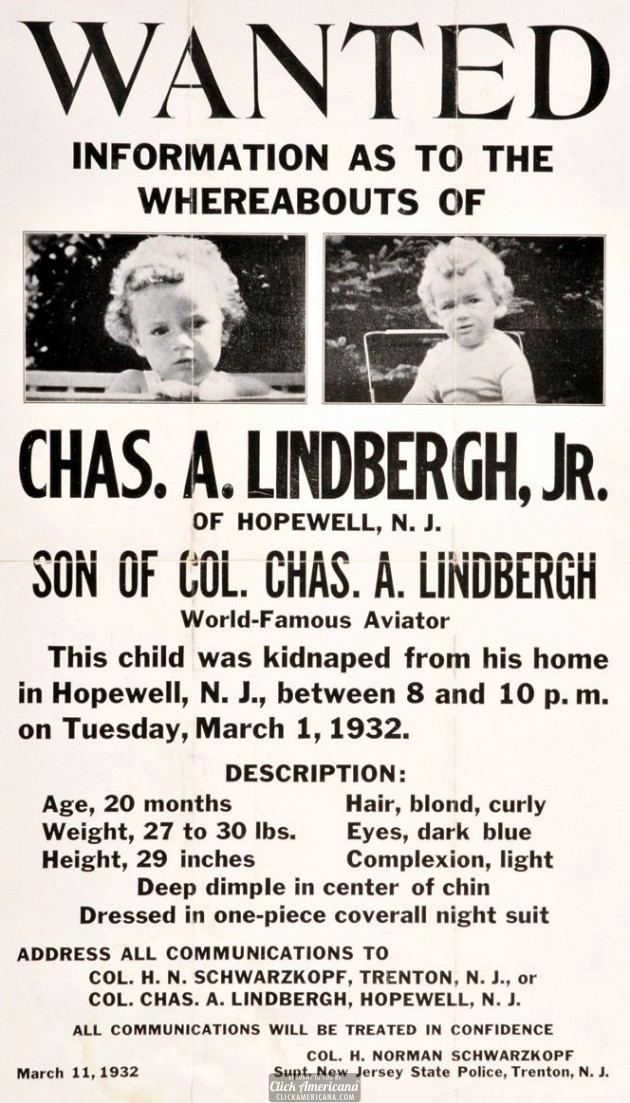

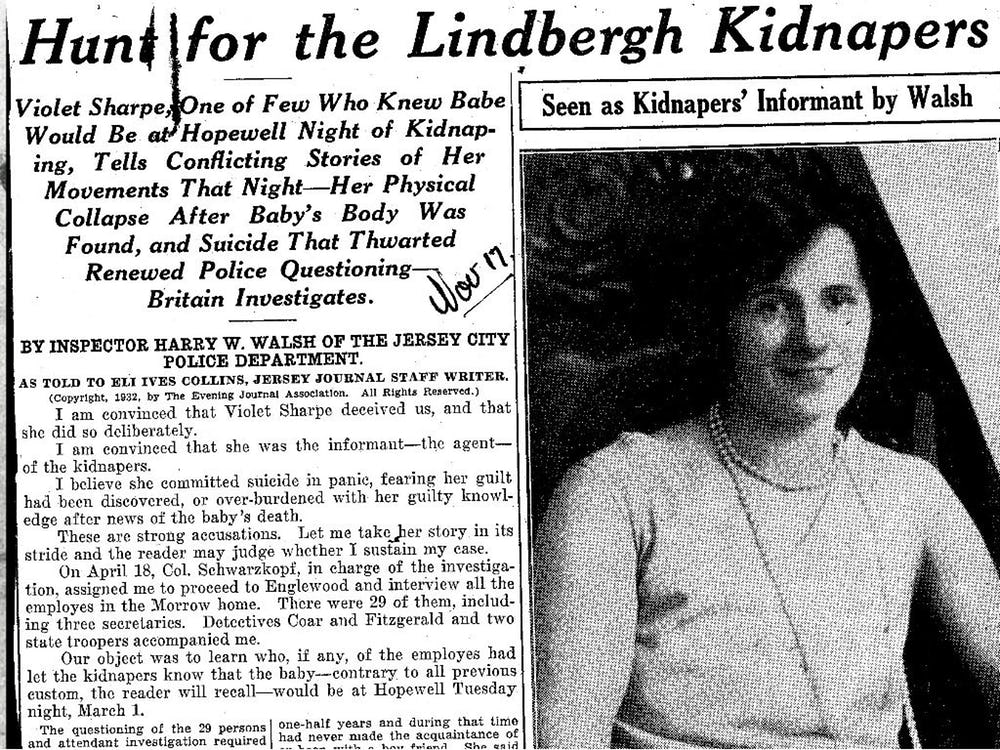

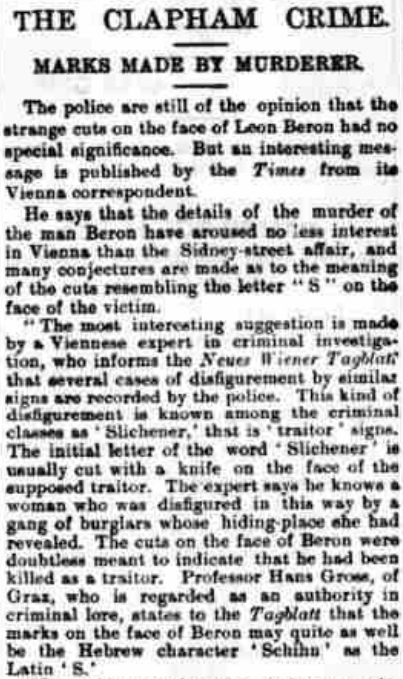

Christie had no formal education during her upbringing but was a polymath and a natural scientist. Her father taught her arithmetic, and she had an inherent understanding of quantity, scale, and proportion. She also taught herself to read and read a range of books and newspapers throughout her life, including the Daily Mirror and the Telegraph. Examples of forensic science in action from these newspapers are shown below to illustrate what Christie was exposed to.

Foundations of Forensic Science

The earliest written accounts of the use of forensic science were in 6th century China. The term “forensics” comes from the Latin “forensis,” which means “of or before the forum.” The primary definition of “forensic” is belonging to, used in, or suitable to courts of justice or to public discussion and debate.

Forensic science, the focus of this post, refers to the application of scientific principles and techniques to matters of criminal justice especially as relating to the collection, examination, and analysis of physical evidence. According to the Canadian Society of Forensic Science,

Forensic science is therefore the application of science, and the scientific method to the judicial system. The important word here is science. A forensic scientist will not only be analyzing and interpreting evidence but also challenged in court while providing expert witness testimony.”

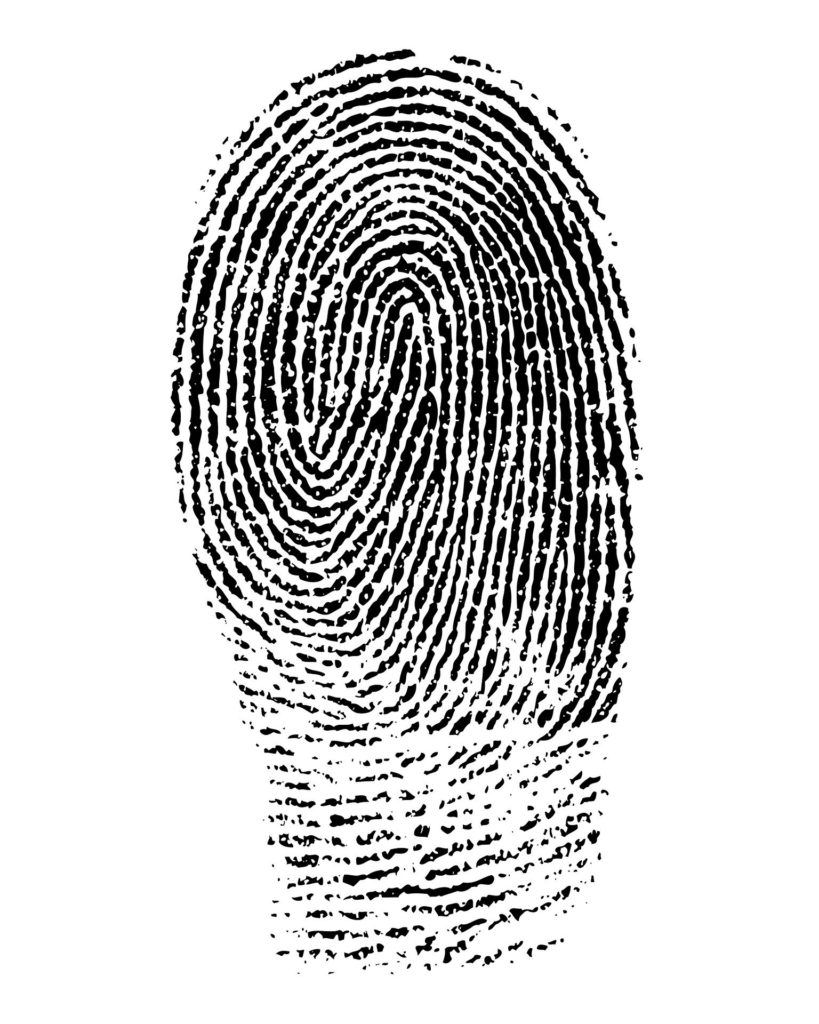

Criminalistics refers to the specific scientific tests or techniques that are used in connection with the detection of crime. Criminalistics is a subset of forensic science and started with the “scientific aids” movement in the UK. An example of criminalistics would be the collection of fingerprints at the scene of a crime by a CSI technician, which are then examined by a forensic scientist with an expertise in fingerprinting.

Forensic Science and Agatha Christie at the Turn of the 20th Century

At the turn of the 20th century, around the time that Agatha Christie was born, the field of forensic science had evolved to suit the need to present evidence in a courtroom, which was (as it is now) primarily done through expert witnesses. The earliest types of witnesses were medical experts, such as a doctor testifying as to the cause of death, but by the end of the 19th century, other scientific fields were beginning to be represented.

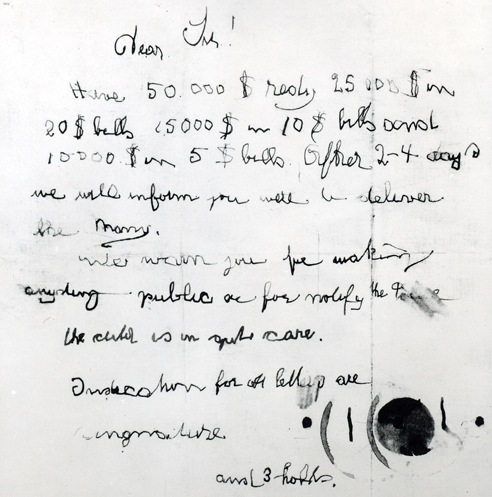

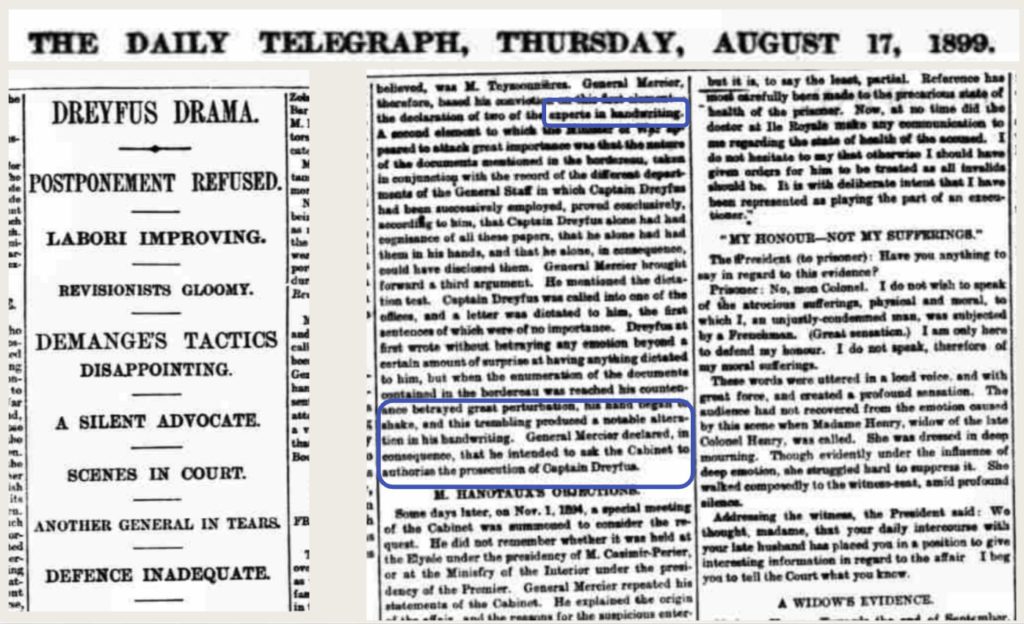

Below is an example from the Daily Telegraph from the Dreyfus trial in 1899 detailing the testimony of a handwriting expert. This was Captain Alfred Dreyfus’s second trial for treason against France, and he was erroneously found guilty based on this expert handwriting analysis. The case is an example of the theoretical nature of many areas of forensic science as well as the influence that the media has in portraying forensic science as a single source of truth. The case was also an example of unchecked antisemitism, which was also present in Christie’s early works though lessened as she matured as an author and a human. Dreyfus was subsequently pardoned and served in World War I.

At this time, a few forensic science techniques were already widely accepted, most notably fingerprinting analysis. One of the first celebrities in forensic science in the UK was Bernard Spilsbury, a Home Office forensic scientist. His authoritative performances in the witness stand, for example at Crippen’s trial, were held as an example until the 1980s. But his celebrity status led the public to conclude that forensic science would provide absolute, unquestionable proof.

Spilsbury gave compelling evidence based on his microscopic examination of human remains recovered in Crippen’s home that a scar on a piece of skin identified the remains as those of Crippen’s wife, whom Dr. Crippen killed and then escaped with his mistress via ship to Canada.

The Crippen case was among the first true crime cases to receive full media coverage complete with descriptions of recent scientific advances such as the wireless telegraph. Christie would have read about the case and its trial, and even used it as inspiration for the historical crime in the 1952 Poirot novel Mrs. McGinty’s Dead.

Also in the 1910’s, Christie began volunteering as a nurse and may have chosen nursing as a career, if she had not become a successful writer. But many of the best scientists are inherently creative, and Christie had a keen interest in science throughout her life. She also married science with her creative writing, for example with her poem “In a Dispensary.”

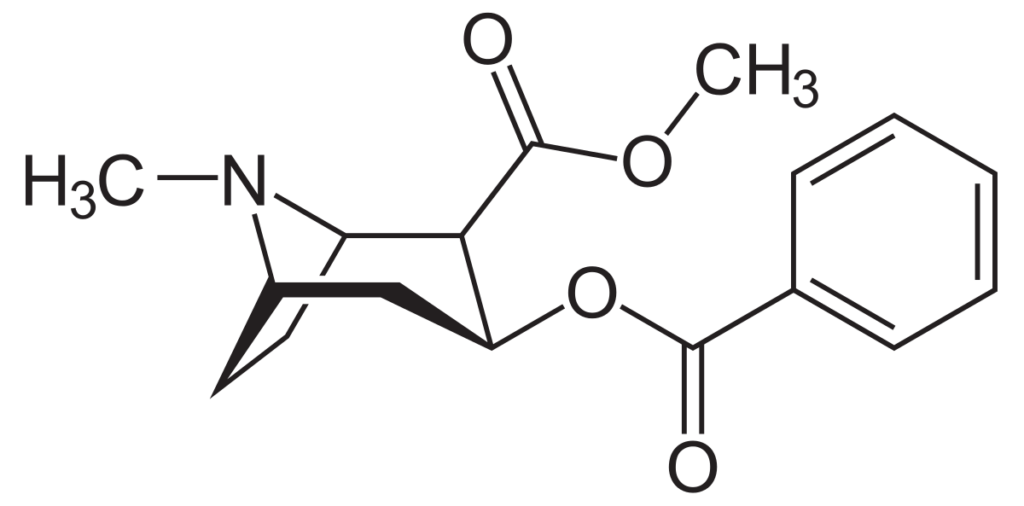

She transitioned from nursing to dispensing (also known as pharmacy) during World War I. As part of her training, she learned chemistry and physics and kept notebooks listing various substances (their appearances and properties) in alphabetical order.

In 1917, she passed 2 of the 3 parts of the Society of Apothecaries’ examination: chemistry and medica (composition of medicines). She passed the practical portion on her second try.

Forensic science to address criminal poisoning cases developed early in natural history, as early as the mid-18th century. In the mid-19th century, the Society of Apothecaries began to require their candidates attend lectures in medical jurisprudence. At this stage, a doctor could harvest samples and organs for testing for the presence of poisons.

Christie’s knowledge from her dispensary training was most applicable to the study of poisons and toxicology. More broadly, analytical chemistry was widely used for extracting metals, manufacturing synthetic dyes, and conducting quality control. Analytical chemistry is an area of applied science that answers the questions about an unknown substance: what is there and how much exists.

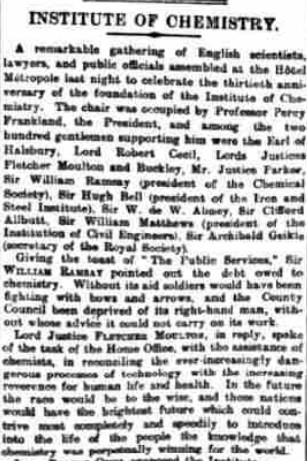

The Institute of Chemistry was founded in 1877 in the UK, which formalized the field of analytical chemistry. Additional formality to scientific careers was introduced in the early 20th century when the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research was established following World War I.

Christie used her knowledge of poisons to craft her first mystery novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, around 1916. The book was not accepted for publication until several years later. In the original draft of the novel, Hercule Poirot revealed the solution while serving as an expert witness in a murder trial, showing Christie’s knowledge of the forensic application of science.

The Relationship Between Mystery and Science

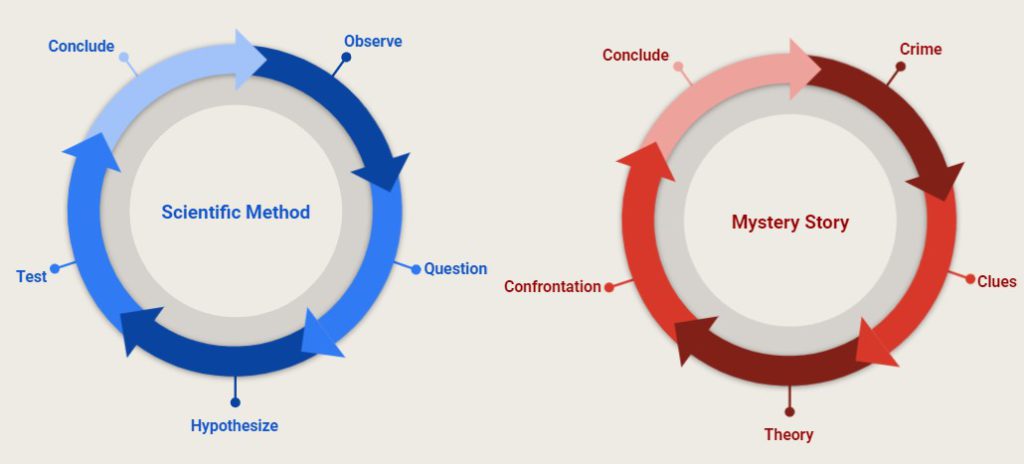

The transition from practical science into mystery writing was a natural one. Essentially, science seeks to solve the mysteries of the universe. Below on the left, this diagram shows the Scientific Method, which is the accepted stepwise process for conducting scientific endeavors. After making observations, a scientist poses a question, which is answered by a hypothesis. A hypothesis is a statement about the question that can be disproven or rejected. The scientist then conducts experiments to test their hypothesis. Once the experiments are complete, the scientist can reject or fail to reject their hypothesis, which leads to a conclusion to their question. It may not be the answer, but it will provide information hopefully leading to the answer eventually. It is a cyclical process that repeats ad infinitum.

Below on the right is a similar diagram showing the structure of a mystery story. Of course, stories can vary in their presentation, but generally every mystery story has a central crime. After the crime has occurred, a detective or other character collects clues to inform a theory of what has happened. When the detective is confident in their theory, there is a confrontation with the criminal. And like science, when the theory is tested, there is a conclusion to wrap up loose ends in the story and perhaps point to future stories.

Christie was not the only author to transition from medical sciences into mystery fiction. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, was a physician, and Richard Austin Freeman, the creator of Dr. John Thorndyke, was educated in medicine. But Christie distinguishes herself with her breadth of knowledge specifically regarding poisons

Forensic Science in the 1920s Through 1940s

The following decades were a period of growth by Christie the author and also in the field of forensic science in the UK. Detectives with Scotland Yard had acknowledged that more knowledge and coordination were required to detect and apprehend criminals. Below is an overview of the key forensic scientists and developments during this important time period, as Scotland Yard worked to incorporate forensic science to solve crimes.

Hans Gross

Toxicology may be the first true forensic science, as the field developed in the 19th century specifically to be used to solve crimes. Somewhat later, crime scene analysis was developed by Hans Gross in his Handbook for Examining Magistrates. His work was practical and addressed how to manage and preserve evidence from crime scenes. However, his work was marred by frequent references to the Romani as criminals. When his handbook was first translated into English, it was done so in the British colony of India and transposed these racist beliefs onto the native tribes. Eventually, newer editions of the work edited out these racist segments. The importance of Gross’s work was its reliance on the materials at a crime scene that could be properly collected and serve as objective “witnesses” to a crime. Crime scene analysis inspired by Gross’s work was adopted by Scotland Yard in the 1930s.

Cesare Lombroso

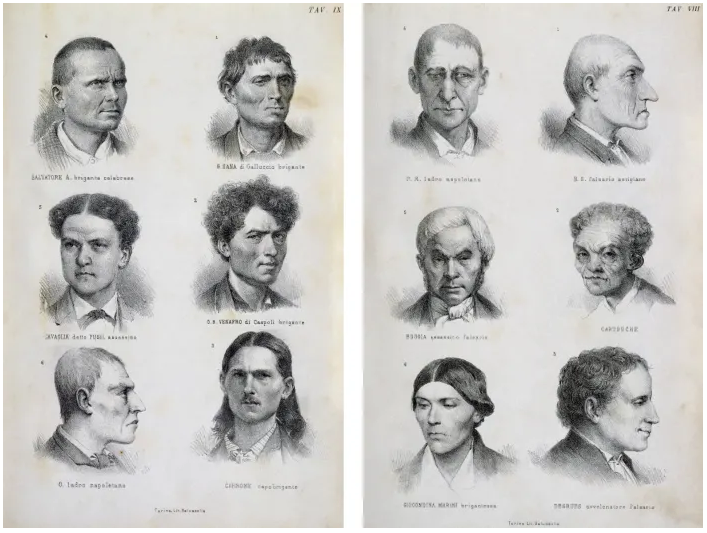

Cesare Lombroso measured and categorized an untold number of skulls in the hopes of quantifying criminality. His work was translated into English in 1927 and introduced the notion of a “born criminal” that could be identified through physiognomy, and examples are shown below on the right. It was never fully accepted in the UK, likely due to Lombroso’s reliance on theory rather than empirical science.

Alphonse Bertillon

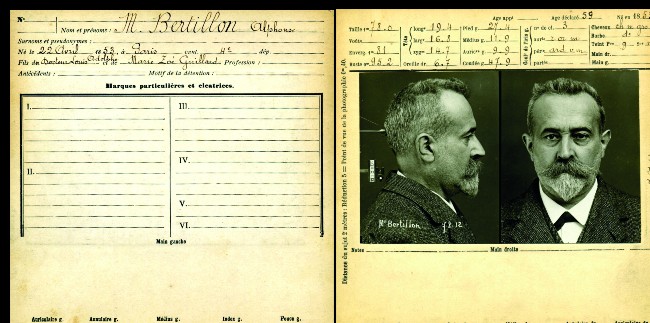

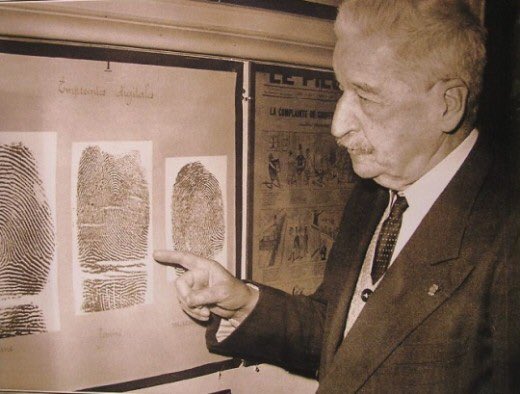

Alphonse Bertillon created the Bertillon System, an anthropometric approach to measuring criminals and criminality, in 1879, but he also pioneered crime scene management and forensic photography. Bertillon developed precise photography techniques of the face and profile of criminals, and his photographic techniques were applied to crime scenes as metric photography, which used physical measuring scales (such as rulers) to provide a permanent and accurate record of the crime scene including the location and size of objects. Although fingerprinting ultimately proved superior to anthropometry in identifying criminals, the 2 techniques were used in concert for many years. And of course, the mug shot technique developed by Bertillon is still in use.

Juan Vucetich and Edward Henry

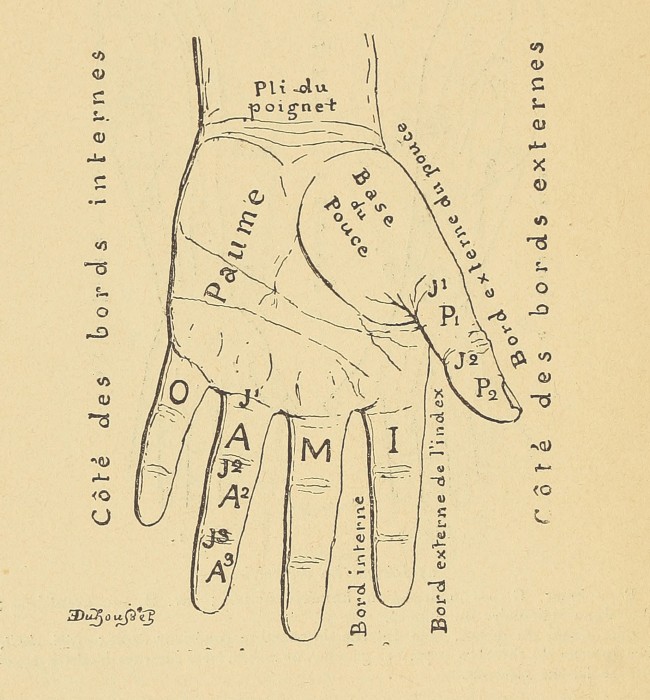

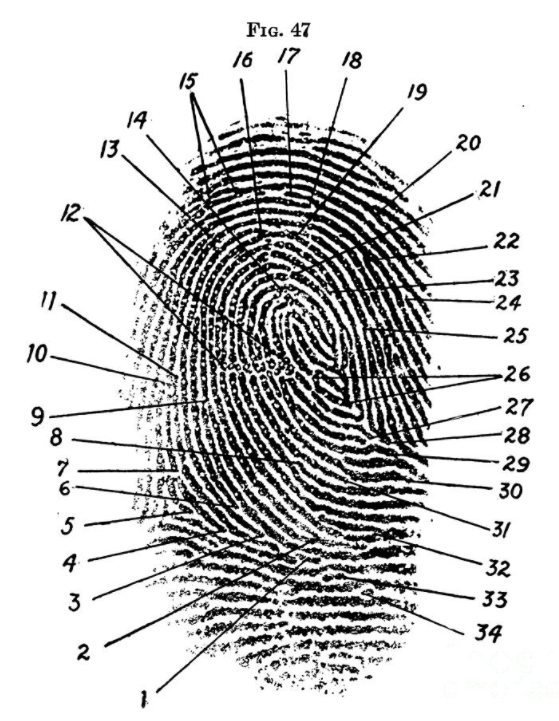

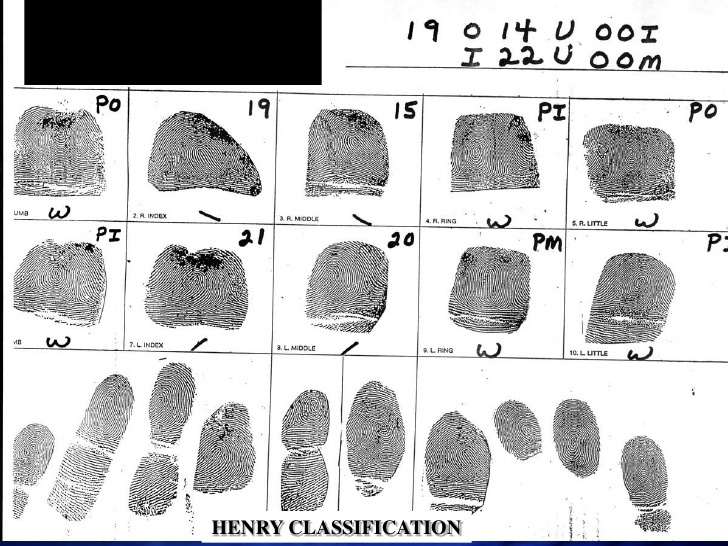

Fingerprinting for criminal identification was first used by Juan Vucetich in 1891 in Argentina. Sir Edward Henry developed a fingerprinting system that was adopted by Scotland Yard in 1901 and was the basis for the US FBI criminal files created in 1924. This adoption followed the recommendation by the Belper Committee of the Home Office to utilize fingerprinting alone for criminal identification. Henry’s system includes subclassification of fingerprints with more than 1024 categories and subcategories. Matches were made through manual examination of fingerprints with a magnifying glass and was therefore not useful if there was not a print in the catalogue to match to, and the system was also flawed by classification errors that could prevent the identification of a print. In the 1960s, the first computer programs for fingerprint identification were based on the Henry system.

Edmond Locard

Edmond Locard was a French forensic scientist with an impressive laboratory in Lyon that was held as an aspirational example to forensic scientists in the UK. Locard was known as the “French Sherlock Holmes” and proffered his exchange principle, which asserted that whenever there is contact between 2 items, there is an exchange of material; this is the basis of several forensic sciences such as fingerprints and fiber analysis.

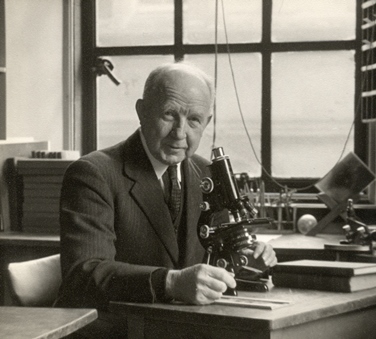

Sydney Smith

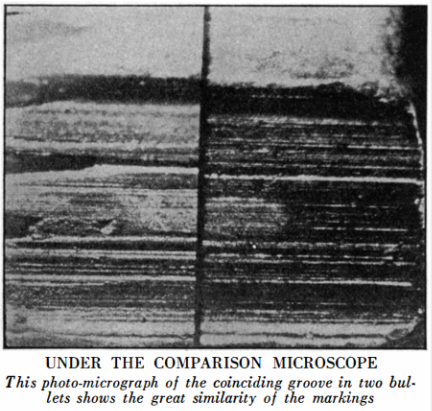

Sydney Smith served as a medicolegal expert for the Egyptian government prior to his appointment as a Professor of Forensic Medicine at the University of Edinburgh. In 1924, he and his colleagues employed one of the earliest uses of ballistics to identify the gun used to assassinate Sir Lee Stack Pasha. Similar to fingerprinting, the unique markings left on a bullet by a particular firearm were evaluated using a comparison microscope.

Alfred Lucas

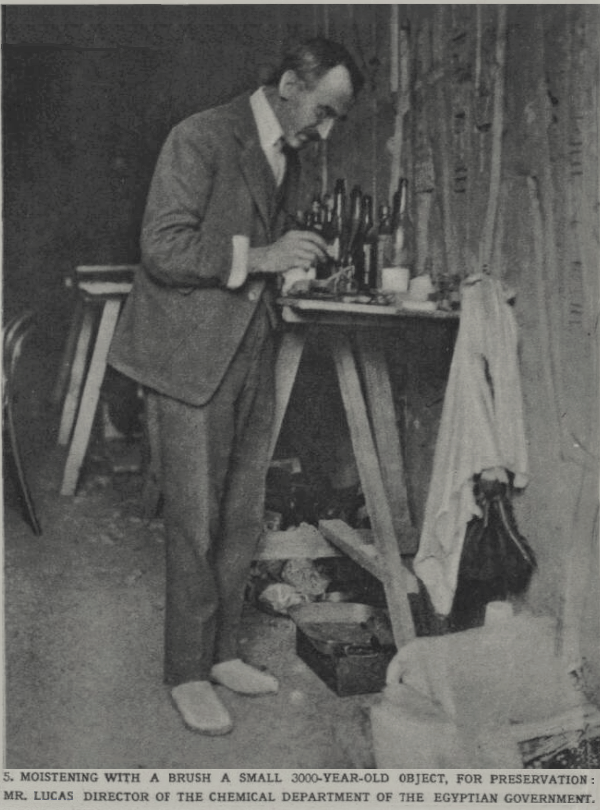

Another early work in the field was Forensic Chemistry and Scientific Criminal Investigation by Alfred Lucas, first published in 1920. Lucas was a British analytical chemist who had worked alongside Howard Carter in his Egyptian archaeological excavations. The book was highly detailed and a basis of forensic science in the UK for several decades. Lucas was also a correspondent of Nigel Morland, a crime fiction writer from the 1930s through the 1970s who would reference Lucas’s work throughout his fiction.

Forensic Science and the Public

The media was a primary source of information about forensic technologies to both the public and criminals. Alfred Lucas stated in Forensic Chemistry, “

...in fact the criminal is becoming so scientific, not only in his work, but also in the means he adopts to escape detection, that a scientist is needed to cope with him, that is to say, a scientist must be set to catch a scientist.”

As early as the Victorian era, there was considerable public interest in crime reporting. At the turn of the century in the UK, the creation of tabloids capitalized on this appetite. The reporting of the Crippen case offers the best study of the role of the press in disseminating knowledge of criminals and forensic science. Most notably, the use of the wireless telegraph in apprehending Crippen was so widely described in the media that scholars have suggested

the Crippen saga did more to accelerate the acceptance of wireless as a practical tool than anything the Marconi company had previously attempted.”

The Departmental Committee on Detective Work for England and Wales

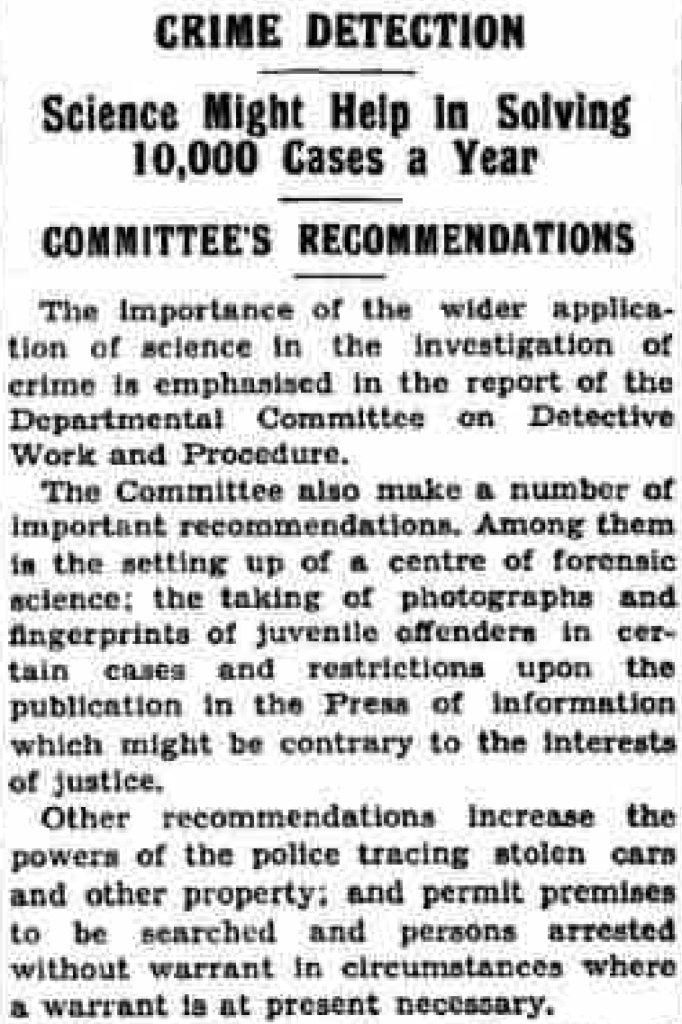

In the 1930s, the Home Office commissioned the Departmental Committee on Detective Work for England and Wales “to inquire and report upon the organization and procedure of the police forces of England and Wales for the purpose of the detection of crime.” Their report was submitted in 1938 and provided substantial evidence of the relationship between scientific training and analysis to the detection of crime. This allowed for the establishment of additional laboratories with the purpose of solving crimes and essentially formalized the field of forensic science.

The Detective Committee report acknowledged that the majority of crimes in the 1930s were against property and not people. Violent crimes (including sexual crimes) comprised about 2.5% of all crimes, violent crimes against property about 19.5%, nonviolent theft about 75%, and forgery about 1%. Burglary and breaking and entering crimes had tripled since the beginning of World War I. The report also acknowledged the ability of criminals to move location and evade detection, and so recommended the centralization of records as well as maintaining adequate local police forces. The Detective Committee report estimated that 4% of crimes (>10,000) would require scientific analysis of evidence.

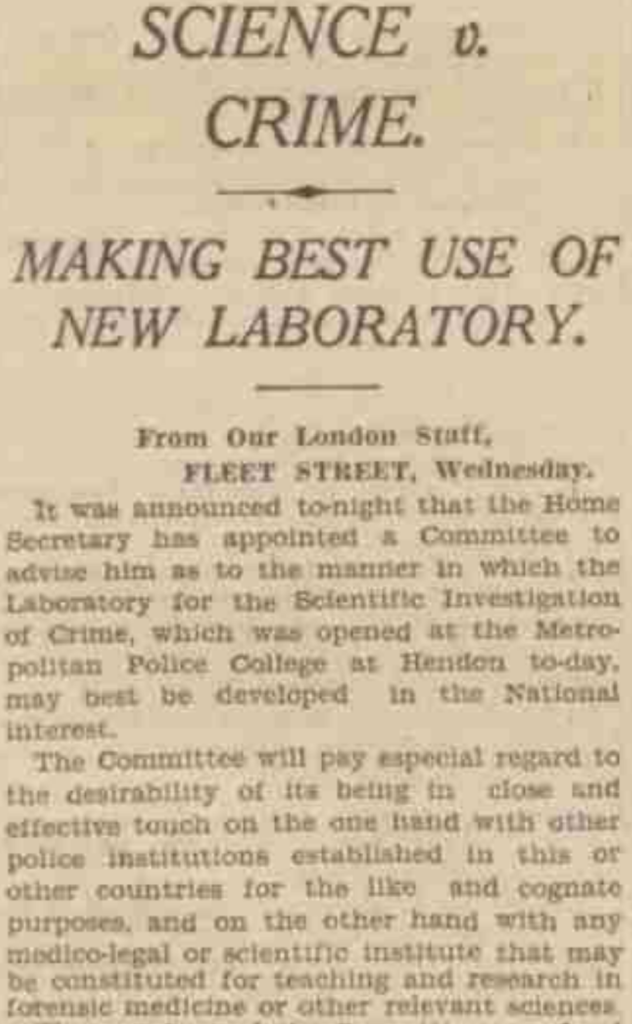

Around the same time, in 1935, the Metropolitan Police opened its first forensic science laboratory in Hendon. However, it initially struggled to work in concert with the police force, and little work was forwarded from Scotland Yard. Coordination between police officers and forensic scientists was a continual challenge in the UK, as there were often class and educational divides between the 2 professions.

In 1946, a public education campaign released a film entitled Science Fights Crime to announce the resumption of detective training courses. The video demonstrated the newest scientific methods in forgery, fingerprinting, burglary, self-defense, identification of suspects, ballistics, and infrared and ultraviolet photography.

Scientific Aids

Forensic science theories evolved along with technology. In 1946, Sir John Maxwell, former Chief Constable of Manchester stated,

...great progress has been made in the application of science as an aid to police work. The introduction of the motor car...the use of wireless, the gradual development of police laboratories to help in crime investigation and the adoption of traffic signal lights are typical examples of the process of mechanization.”

This was the era of “scientific aids” in policing.

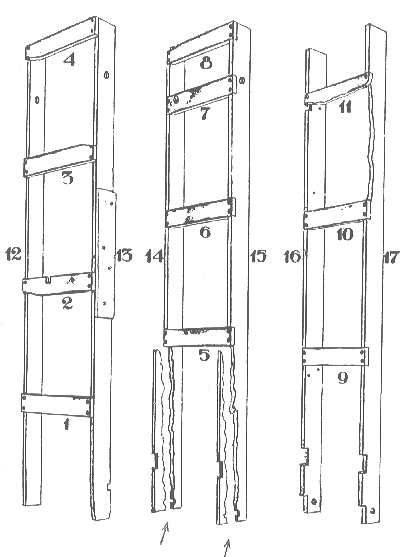

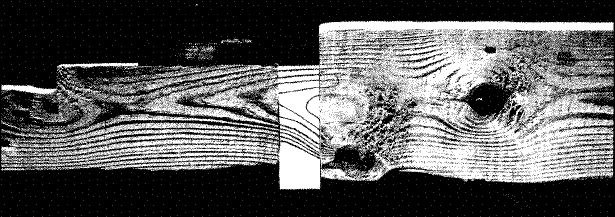

Throughout this era, “scientific aids” were developed and promoted for use by police officers. These are roughly equivalent to “criminalistics” and were to be used by police officers during their investigation of crimes to help allow for objectivity in the processing of crimes. An instructional pamphlet published in 1936, Scientific Aids to Criminal Investigation, provided highly detailed descriptions for what to do at a crime scene. There were several parts to this publication, a few of which are shown here.

The goal of scientific aids can be described by the following quote:

Scientific evidence, when properly interpreted, may thus provide, in certain classes of cases, a kind of proof which never lies and never alters its tale, and which, if placed before the Court by a competent witness, can be seen by Judge and jury for themselves.”

Forensic Science from the 1950s Onwards

As with many other fields, the development of forensic science paused during World War II, which stagnated scientific advancement for many years. According to author Alison Adam, “the development of the forensic science profession was complex and piecemeal.” The forensic science principles described in this presentation continued to be used throughout the remainder of Agatha Christie’s life, with few notable breakthroughs until the mid-1980s with the advent of DNA identification.

As a result of writing crime books one gets interested in the study of criminology. I am particularly interested in reading books by those who have been in contact with criminals, especially those who have tried to benefit them or to find ways of what one would have called in the old days ‘reforming’ them–for which I imagine one uses far more grand terms nowadays!”