**Contains major plot spoilers for The Affair at the Victory Ball.**

A Singular Dedication

This dedication by Agatha Christie in her collection of short stories The Mysterious Mr. Quin is wholly unique because it marks the only time Christie dedicated one of her works to one of her fictional characters. It is apposite, however, as Harley Quin was probably her favorite among her creations. In her Autobiography, Christie states,

Actually my output seems to have been rather good in the years 1929 to 1932: besides full-length books I had published two collections of short stories. One consisted of Mr. Quin stories. These are my favourite. I wrote one, not very often, at intervals of perhaps three or four months, sometimes longer still. Magazines appeared to like them, and I liked them myself, but I refused all offers to do a series for any periodical. I didn’t want to do a series of Mr. Quin: I only wanted to do one when I felt like it. He was a kind of carry-over for me from my early poems in the Harlequin and Columbine series.

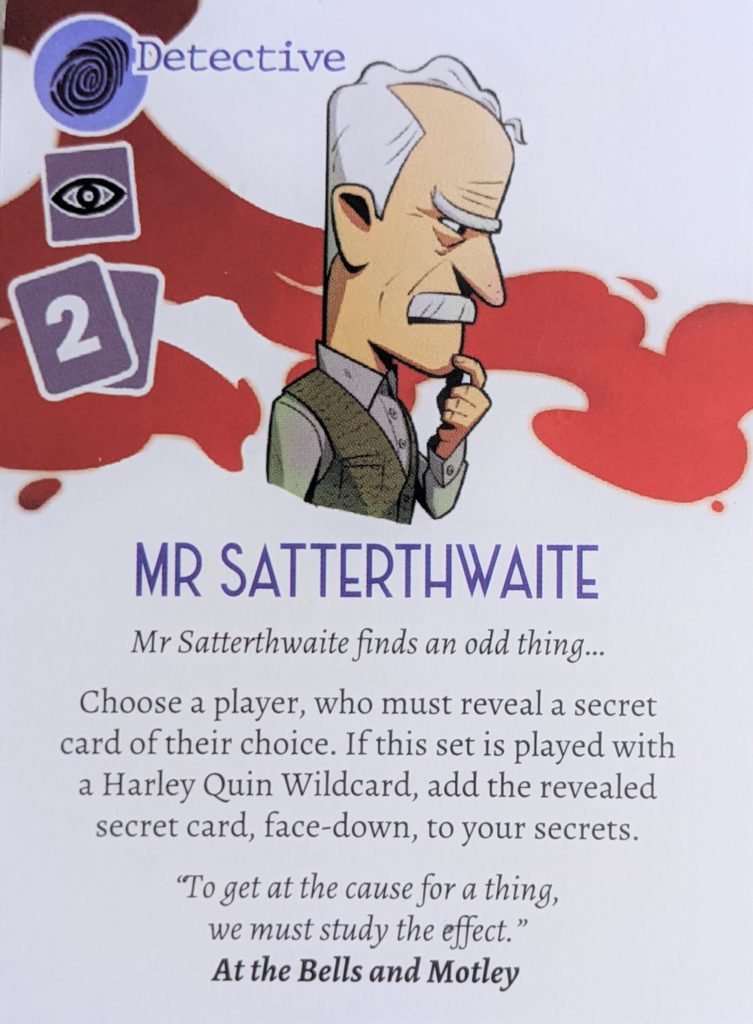

Unlike Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, Harley Quin is not a detective. Rather he is an ephemeral being, arriving at the scene of mysterious circumstances (often involving romantic entanglements) to guide Mr. Sattherthwaite (who could be considered the detective in stories involving Mr. Quin) to the truth about the situations. Although he wears a typical dark suit, it is often described that the light hits him in certain ways to produce effects of a colorful motley or black domino mask. Christie continues,

Mr. Quin was a figure who just entered into a story--a catalyst, no more--his mere presence affected human beings. There would be some little fact, some apparently irrelevant phrase, to point him out for what he was: a man shown in harlequin-coloured light that fell on him through a glass window; a sudden appearance or disappearance. Always he stood for the same things: he was a friend of lovers, and connected with death. Little Mr. Satterthwaite, who was, as you might say, Mr. Quin’s emissary, also became a favourite character of mine.

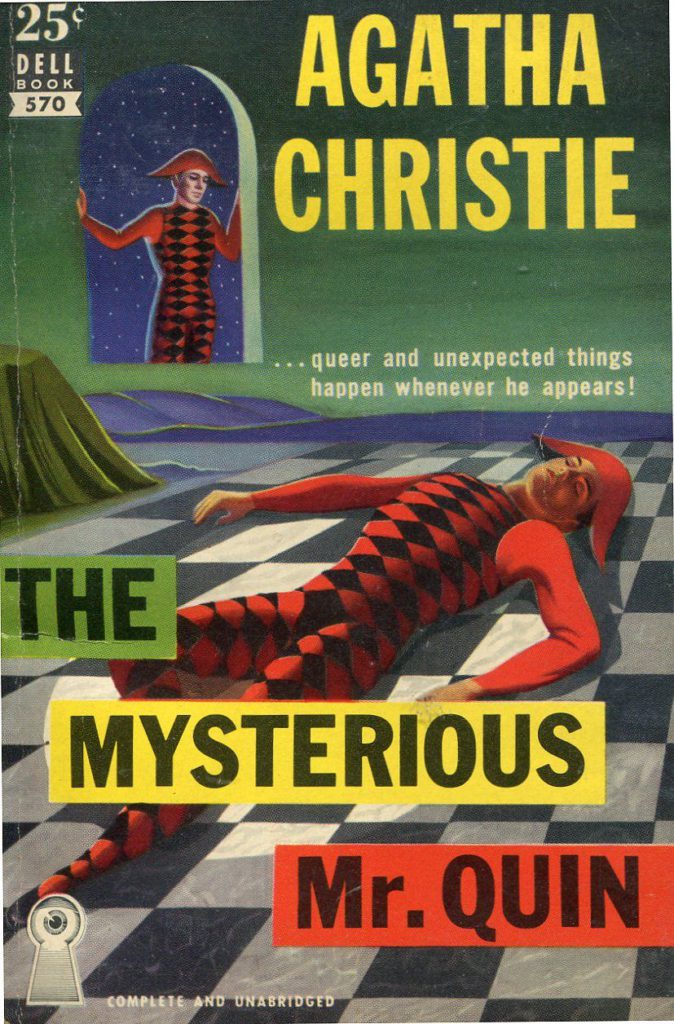

The Mysterious Mr. Quin was published in 1930, shortly after the death of Christie’s brother Monty from a stroke possibly related to wounds suffered in World War I.

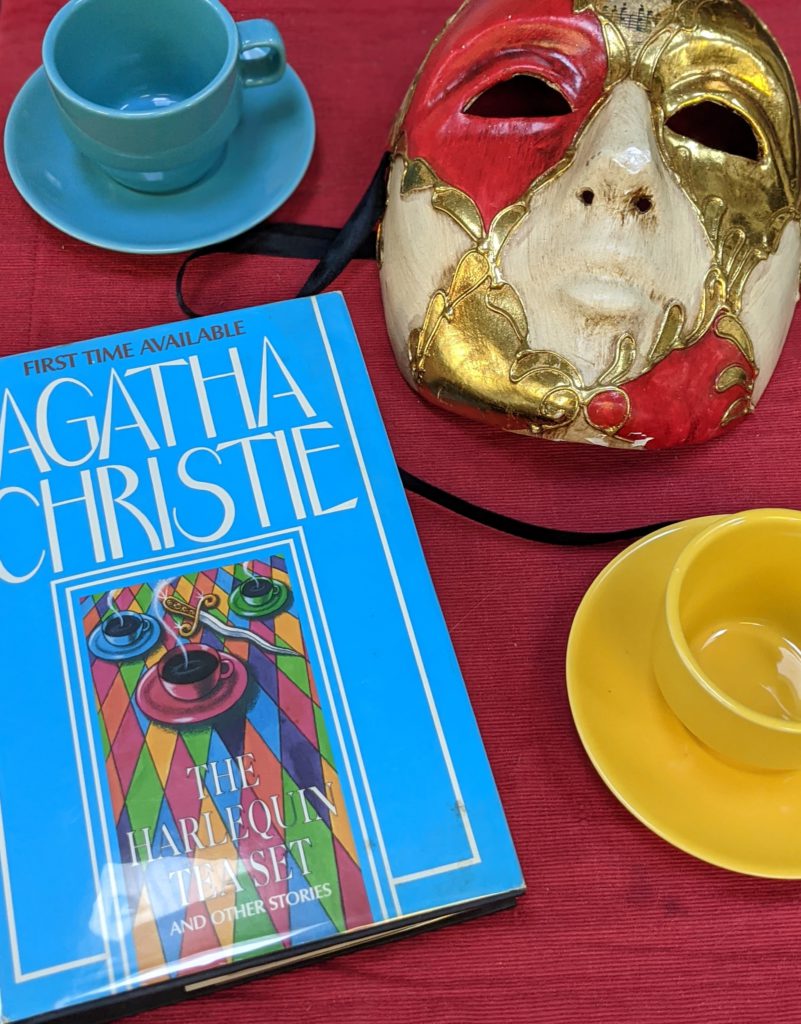

The character of Harley Quin only appeared in 14 stories, assembled into one collection (The Mysterious Mr. Quin) and as part of other collections (The Harlequin Tea Set and Problem at Pollensa Bay and Other Stories). Apart from a silent movie in 1928, there has never been a cinematic or television adaptation of the works, and Harley Quin remains one of Christie’s lesser known characters.

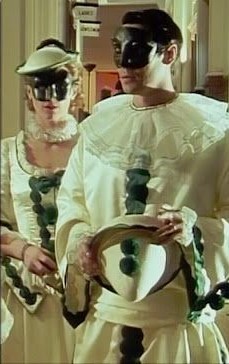

Christie and the Harlequinade

As mentioned in What’s in a Dame?, Christie participated in amateur theatricals in her youth, and a common performance piece at the time was the Harlequinade. Derived from the Italian Commedia dell’Arte, the Harlequinade as a pantomime, play, or ballet tells the story of Harlequin (from the Italian “Arlecchino”), a servile rogue with a predilection to aid lovers with the help of magic and invisibility. He romantically pursues Columbine, an intelligent and compassionate servant. His rival for her affections is Pierrot, who downplays his disappointment when spurned by playing tricks and pranks. The character of Pierrette was a female counterpart to and love interest of Pierrot. Punchinello and Pulcinella may also be servants but more often seem to be the masters in a situation, imposing figures with long noses and broad bellies. The Harlequinade would tell a variety of stories with this cast of characters, often involving some scheme to separate Harlequin and Columbine, and Harlequin would use a magical stick called a “slapstick” to resolve the silly situations – this is the origin of the term slapstick humor.

Pierrot was traditionally played by an actor without a mask and wearing white make-up, which is thought to be the origin of white clown make-up. Harlequin was traditionally masked with a dark brown or black mask, suggesting African influences on the character but more likely related to systemic racism within theatre and society in relation to the character of a servant. Punchinello appears to be the origin of the character Punch from Punch and Judy puppet shows.

Inspired by these theatrical scenes, young Agatha composed a great deal of poetry in her childhood. Some of the poems she wrote around age 17 were published in The Road of Dreams in 1924, including verses about Harlequin, Columbine, Pierrot, and Pierrette; the young Christie even set her Harlequin poems to music. “Harlequin’s Song” describes the character with,

I pass

Where’er I’ve a mind,

With a laugh as I dance,

And a leap so high,

With a lightning glance,

And a crash and a flash

In the summer sky!

I come in the wind,

And I go with a sigh…

And nobody ever sees Harlequin,

“Happy go lucky” Harlequin,

Go by…

[…]

I must play my part…

For never a soul has Harlequin,

Happy go lucky Harlequin,

Only a broken heart…

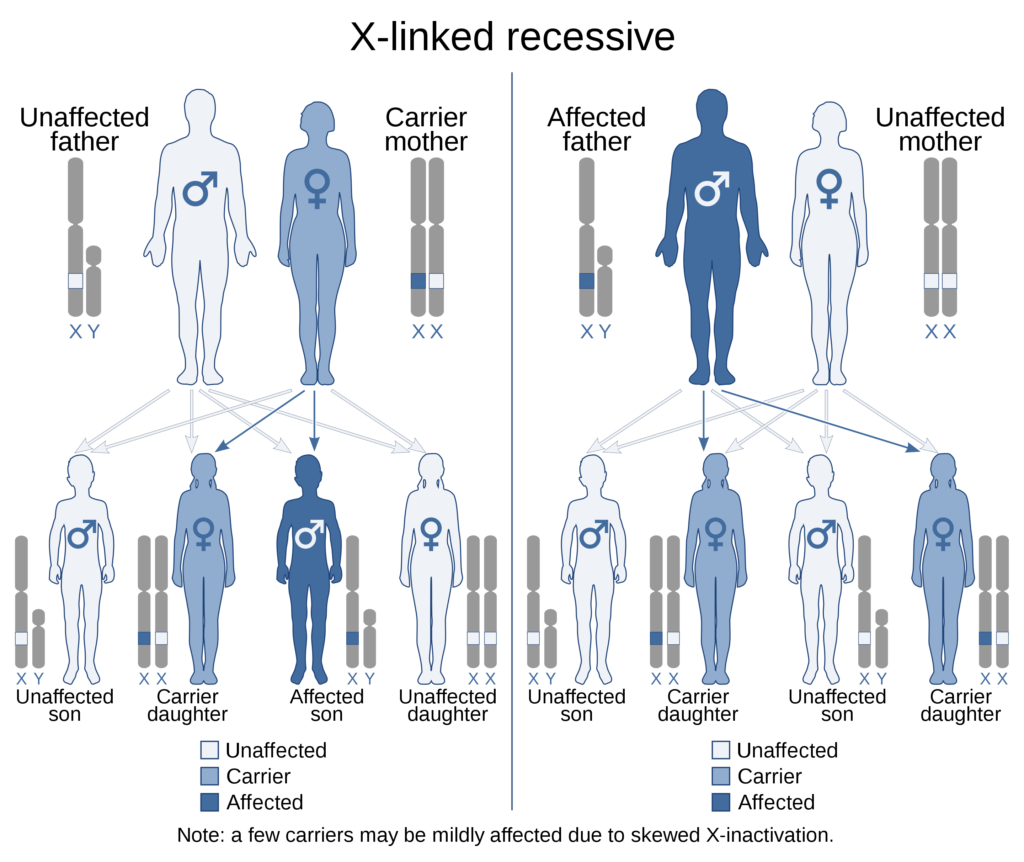

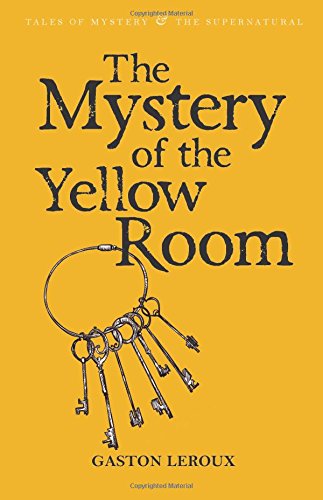

Christie’s grandmother also owned a set of Dresden figurines from the Italian comedy, which are still part of the family’s collection. Drawing inspiration from her love of this set of characters, particularly Harlequin, Christie included them (and a similar set of figurines) in her first short story to feature Hercule Poirot, The Affair at the Victory Ball. The story was published in Sketch in 1923 and tells the story of the murder of Lord Cronshaw at the Victory Ball, which was followed closely by the death of the actress Coco Courtenay by cocaine overdose.

A Victorious Affair

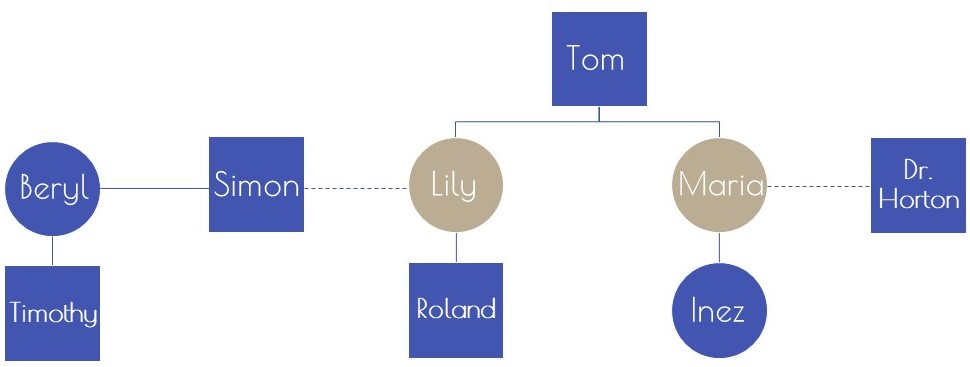

Lord Cronshaw, 25 years of age, was rumored to be engaged to Ms. Courtenay. The pair attended the Victory Ball, dressed as Harlequin and Columbine, in the company of Punchinello (Lord Eustace Beltane, uncle to Cronshow who would inherit his title), Pulcinella (Mrs. Mallaby, an American widow), Pierrot (Chris Davidson, an acting friend of Coco’s), and Pierrette (Mrs. Davidson, Chris’s wife), in costumes inspired by Lord Beltane’s figure collection. The mood was tense between Cronshaw and Courtenay, who requested Chris Davidson escort her home following dinner. After accompanying the tearful actress home, Davidson returned to his flat in Chelsea.

At the Ball, Lord Cronshaw was scarcely seen by the party for the rest of the evening until 1:30 a.m., when he was spotted by a Captain Digby. He asked Lord Cronshaw to rejoin the group, but he had not done so after several minutes. A small search party was formed with Digby, Mrs. Davidson, and Mrs. Mallaby, who discovered Cronshaw stabbed to death in the supper room. On his body was a small enamel box half filled with cocaine and with the name “Coco” inscribed in diamonds. Also discovered tightly clenched in the Lord’s fist was a small green pompon, with ragged threads as though it had been pulled forcefully from its source. The next morning, the body of Coco Courtenay was found in her bed, her death due to an accidental or intentional overdose of cocaine.

These facts of the case are related to Hercule Poirot by Chief Inspector Japp, whose highest talent, according to Captain Hastings, “lay in the gentle art of seeking favours under the guise of conferring them!” Poirot visits Lord Beltane to view the original sculptures and the Davidson home to view the Pierrette costume, which had green pompons. At the conclusion of this investigation, Poirot arranges for a Harlequinade of his own, hiring actors to portray each of the members of the Cronshaw party. Through this elaborate reconstruction, Poirot reveals that Chris Davidson had killed Harlequin and worn a duplicate costume to pose as Lord Cronshaw at 1:30 a.m., several hours after the original Harlequin had been murdered.

Central to the dispute between Davidson and Cronshaw was the use of cocaine by Ms. Courtenay. Lord Cronshaw strongly disapproved of the use of the drug and had demanded Coco’s supply earlier in the evening; therefore, Coco’s enamel box was found on his body. Davidson, who supplied cocaine to Coco, murdered Cronshaw to prevent his exposure as a drug trafficker. While escorting Coco home, he was able to provide her with more cocaine, likely encouraging her to take a larger dose out of spite for Cronshaw’s objections. The tragic result was the death of the young actress, as well.

By viewing the figurines, Poirot was able to ascertain that the elaborate rump and ruffle of the Punchinello costume would have prevented Lord Beltane from changing into the Harlequin costume without assistance. The two women were eliminated because Cronshaw was stabbed with a dull table knife, which would have required considerable strength. And upon visiting the Davidson’s house, Poirot noted that the green pompon missing from the Pierrette costume was cut with scissors rather than being torn off, as the pompon in the fist of Cronshaw was; therefore, the pompon was from Pierrot’s costume. These facts pointed directly to Chris Davidson as the perpetrator, who stabbed Cronshaw shortly following dinner and before returning Coco Courtenay home. Presumably, Davidson had a second Harlequin costume made before the Victory Ball expressly for the commission of his crime, but this is not detailed in the story.

True Crime Inspiration

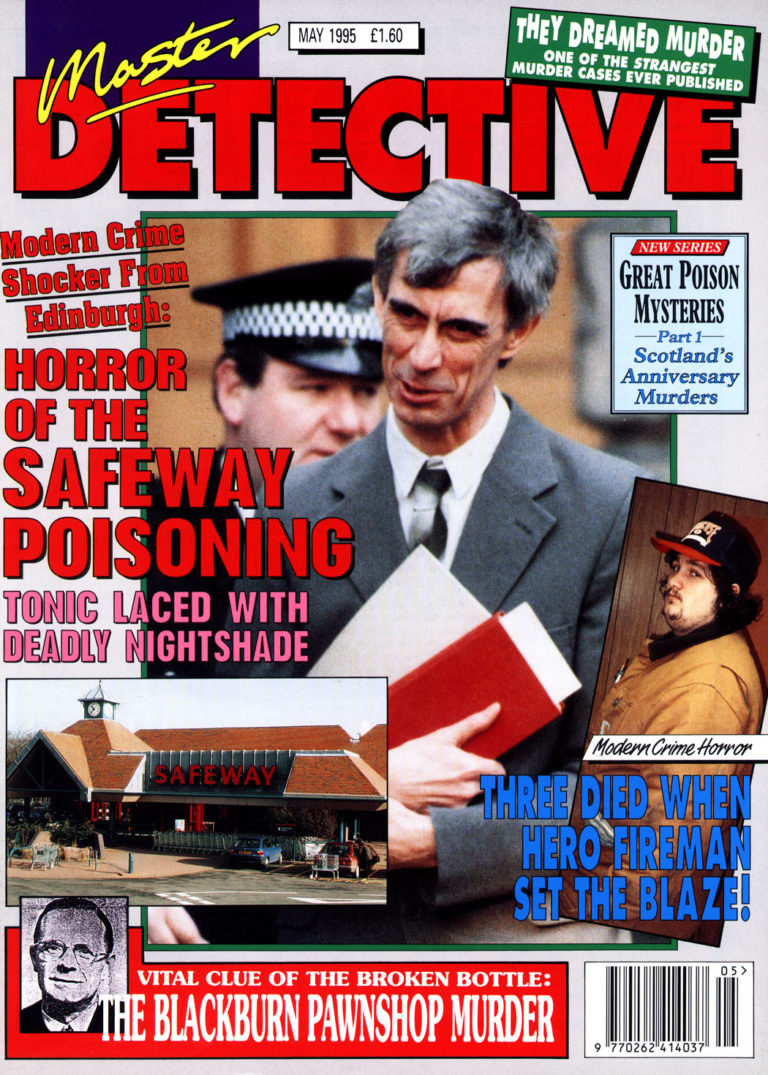

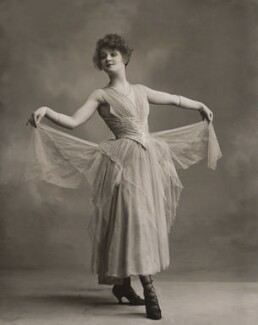

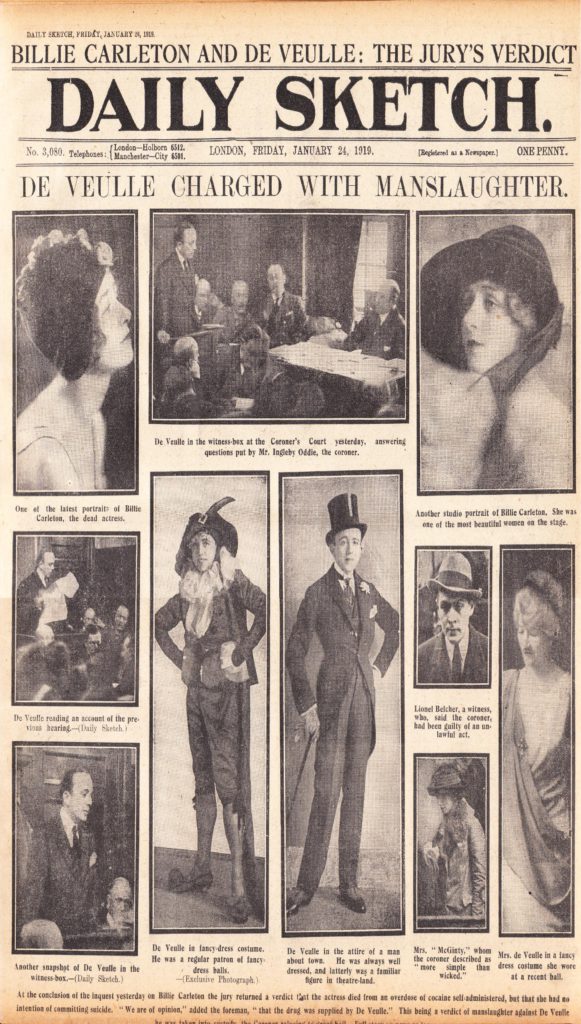

This story was very obviously inspired by the death of Billie Carleton (whose given name was Florence Leonora Stewart), a young actress who died from a cocaine overdose after attending a Victory Ball at the Royal Albert Hall in 1918. Carleton was close friends with Reginald DeVeulle, a dressmaker who reportedly hosted opium parties at his house. DeVeulle, dressed as Harlequin, attended the Victory Ball in the company of his wife Pauline (costume unknown). While at the Ball, DeVeulle allegedly provided a supply of cocaine in a small silver or gold (reports vary) box to the actor Lionel Belcher to pass to Carleton.

After the festivities at the Ball, Belcher and two other actresses, Olive Richardson and Irene Castle, returned to Carleton’s apartment to continue their revelry. It is not known what exactly transpired, but Carleton retired to bed early in the morning, and the others returned to their respective homes. Later in the morning, Carleton’s maid noticed she had stopped snoring; the maid was unable to wake her, and she was pronounced dead a short time later.

Carleton’s death was ruled to be the result of cocaine overdose. The police and public focused on her decadent lifestyle, as she was known to attend opium parties and her reputation had cost her at least one role. Looking to blame a “foreign” influence on her behavior and death, Carleton’s friend and costumer Reggie de Veulle, who allegedly supplied her with cocaine, was ruled to be culpable for her death at the coroner’s inquisition but then acquitted on a formal charge of manslaughter; however, he was charged with supplying cocaine to Carleton. A husband-and-wife duo, Lo Ping Yu and Ada Lo Ping, also received several months of jail time for their roles in supplying opium to the dead actress, among others.

Christie was no doubt inspired by this sensational story from a Victory Ball in 1918. However, her story added the murder of Lord Cronshaw in the guise of Harlequin. Cronshaw adamantly opposed drug taking and was murdered for his beliefs, so this appears to be a way for Christie to reclaim one of her favorite characters as a noble martyr after being used as a costume by a perceived villain such as de Veulle.

Christie even borrowed the name “Cronshaw” from a previous criminal lawsuit that involved Reggie de Veulle, where one of the victims was named William Cronshaw.

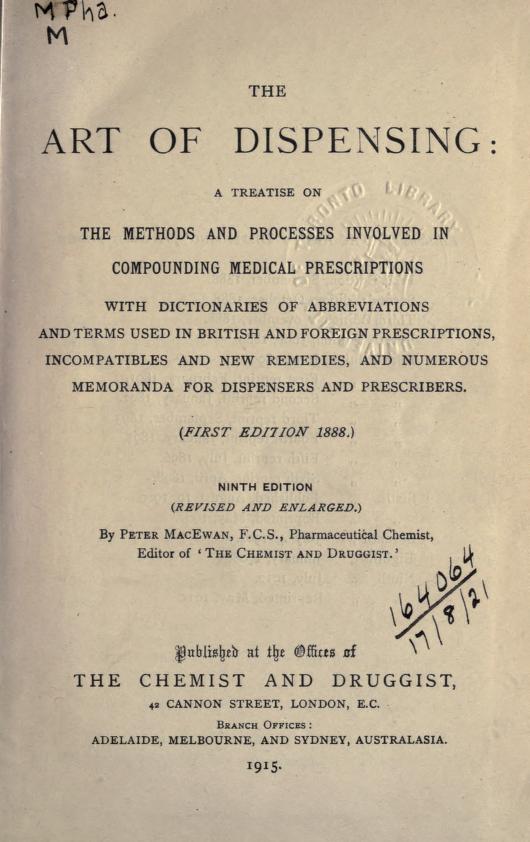

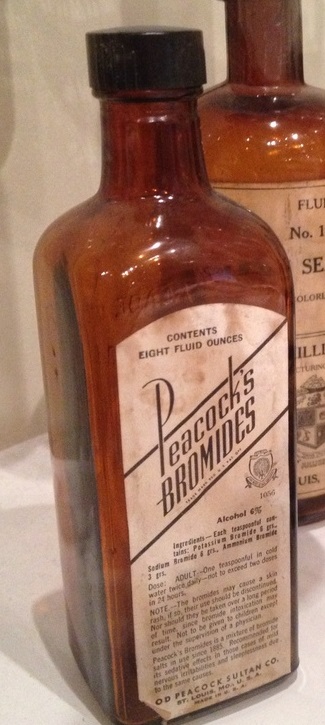

Cocaine possession was illegal in Britain following the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, which was passed in 1916.

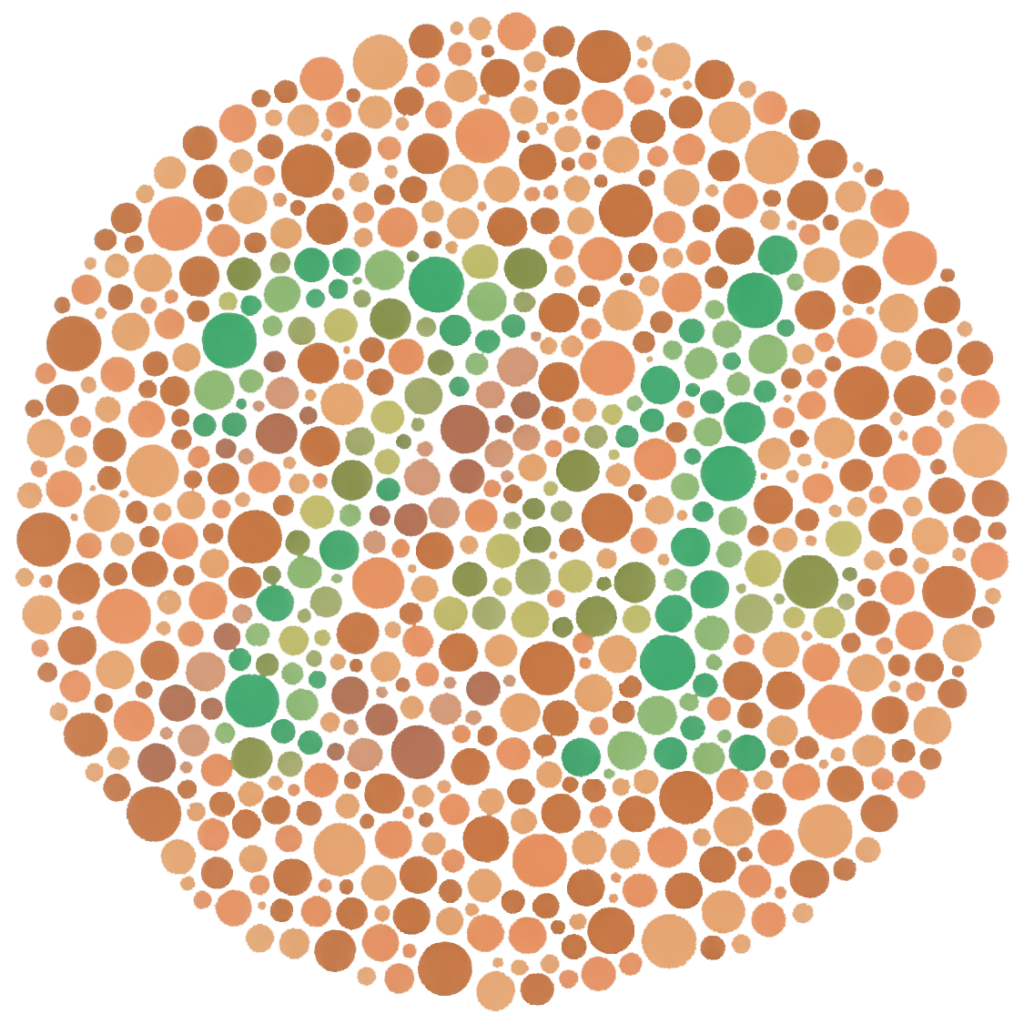

Cocaine use is featured in several other Christie novels, including Peril at End House, Hickory Dickory Death, and the Labours of Hercules. Christie seems to have some sympathy for addicts, but her knowledge of the drug’s effects was more often used to typify the questionable morality of some of her characters.

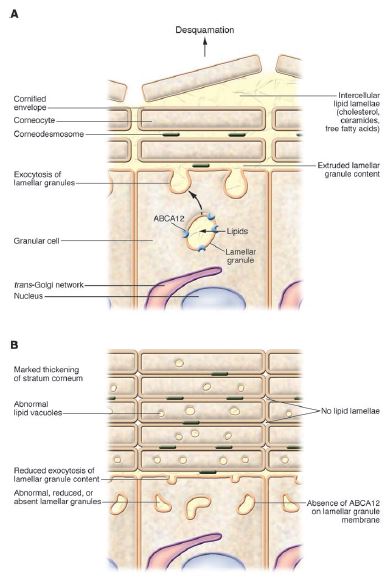

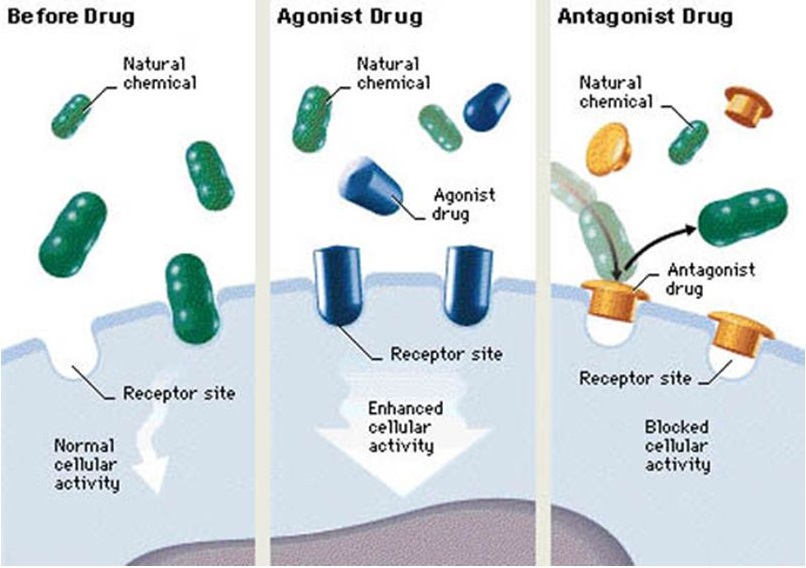

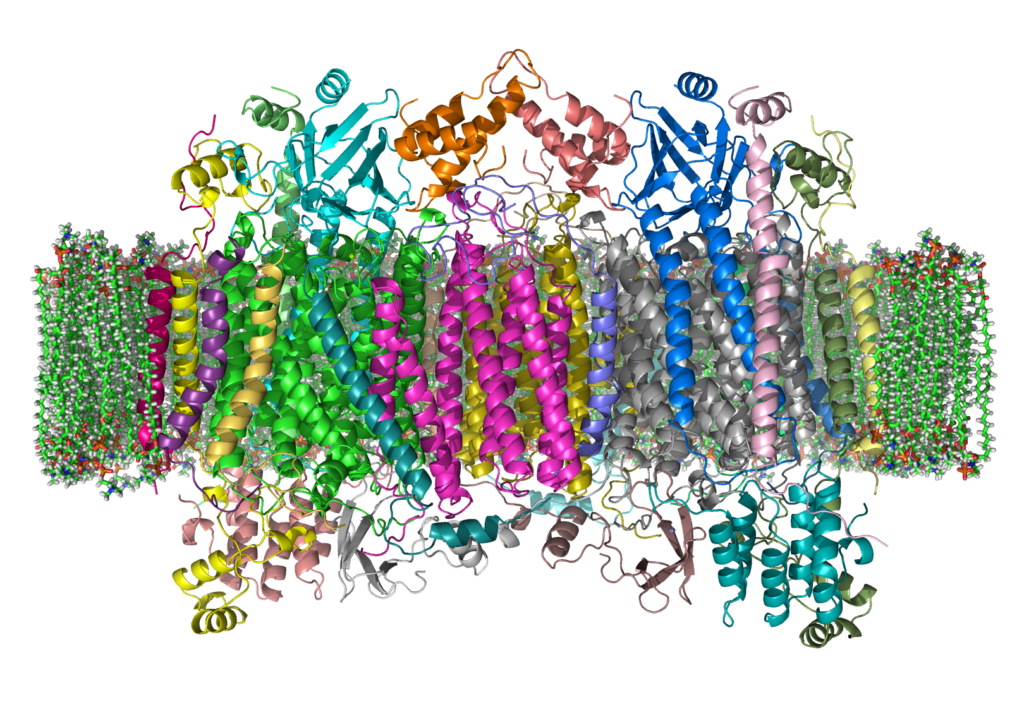

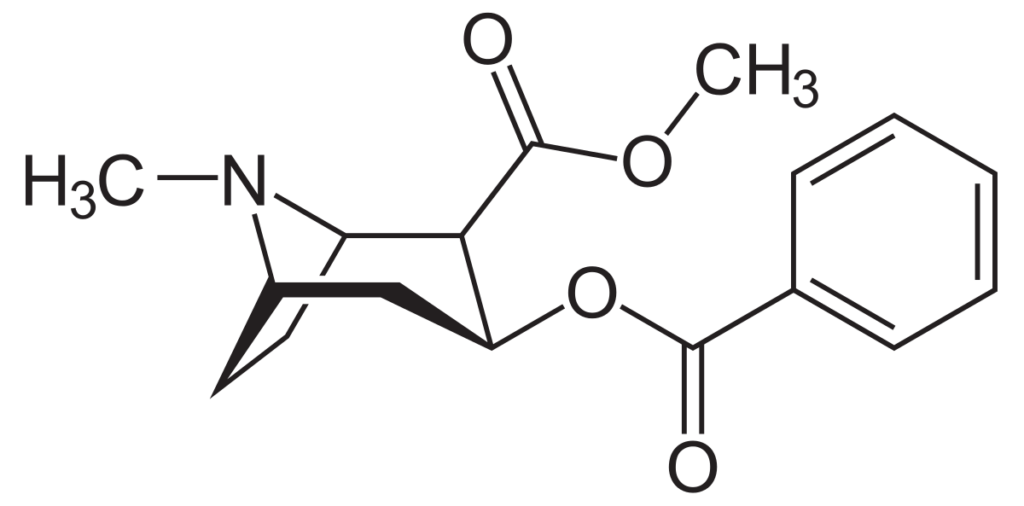

Physiological Effects of Cocaine

Cocaine is a tropane alkaloid. It exerts physiological effects by binding proteins within the body, most notably the serotonin transporter, dopamine transporter, and norepinephrine transporter. These three transporters are involved in the transmission of the respective neurotransmitters from neuron to neuron in the central nervous system. When cocaine binds, the reuptake of the neurotransmitters is reduced or eliminated, causing prolonged stimulation of the downstream neurons.

Inhibition of the reuptake of the neurotransmitter serotonin is the primary function of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are popular antidepressant medications.

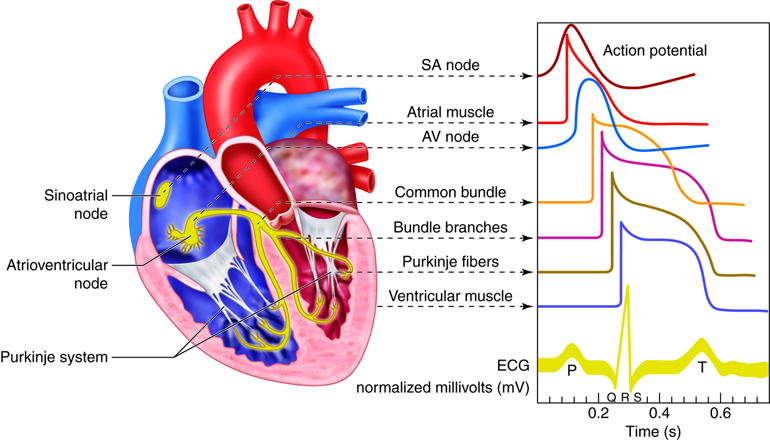

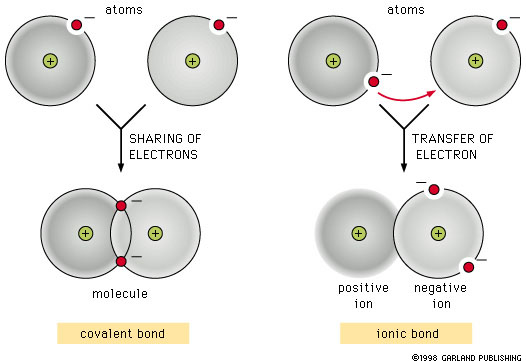

Additionally, cocaine binds to voltage-gated ion channels in the heart, which can result in cardiotoxicity. These channels are present on cellular membranes and control the amount of electrolytes present within cells versus between cells. Electrical changes in the cellular membranes control whether the channels are open or closed. Therefore, an interruption in the function of these channels can lead to deadly electrolyte imbalances.

Electrolytes are ionic (or positively or negatively charged) forms of mineral elements, for example, sodium (+1), potassium (+1), and calcium (+2).

Research has shown that the interaction of cocaine with dopamine receptors is the primary mechanism that drives addiction. In animals genetically manipulated such that their dopamine receptors do not bind cocaine, addictive behaviors do not manifest when the animals are provided and/or deprived of cocaine. However, the interaction between cocaine and the serotonin receptor may cause convulsions, so the displacement of serotonin does play a role in cocaine toxicity. Lastly, the inhibition of norepinephrine signalling by cocaine can lead to rapid increases in blood pressure.

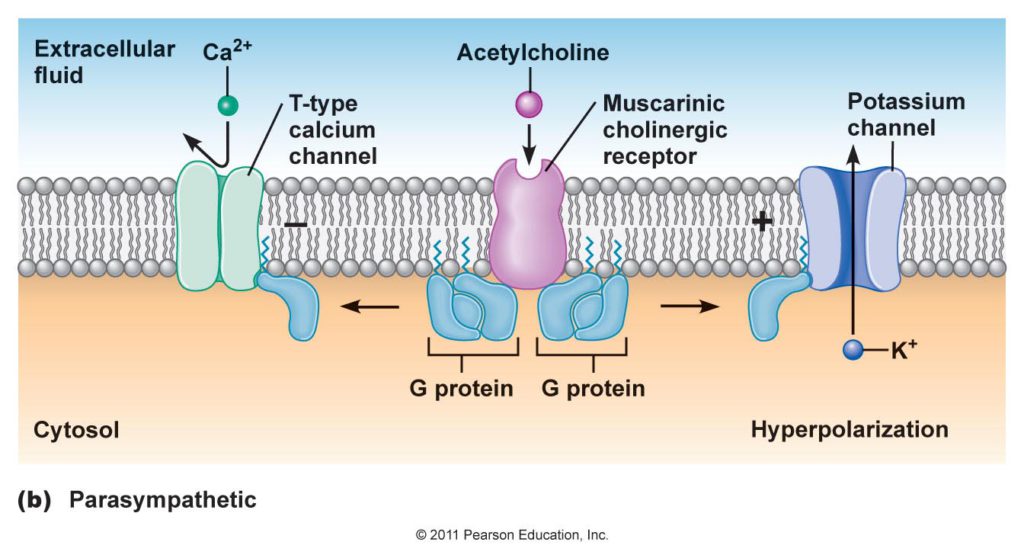

Cocaine also interacts with cholinergic receptors and prevents reduction in heart rate. This interaction would cause an increase in heart rate (similar to atropine as described in Tuesday Night Fever). Coupled with the effect on voltage-gated channels and the increase in blood pressure from norepinephrine inhibition, damage to the heart is a central component of cocaine toxicity. Because the neurotransmitter receptors have a higher affinity for cocaine (in other words, cocaine can bind strongly at lower concentrations), the central nervous system is affected first; for example, the user begins to have seizures. With higher doses or concentrations of cocaine, the voltage-gated ion channels are then affected, and the cardiotoxic effects of cocaine are seen. The interference of cocaine with voltage-gated sodium, potassium, and calcium channels will cause cardiac arrhythmias, which are abnormal changes in heart rate. These arrhythmias can cause sudden cardiac death in cocaine users, even without any pre-exisiting cardiac conditions.

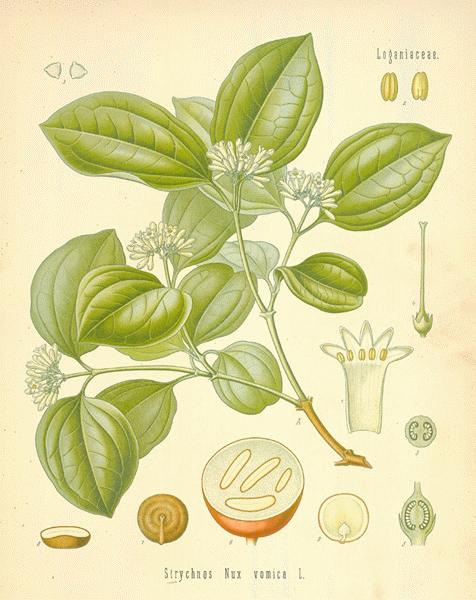

Christie does not provide specific details of Coco Courtenay’s death (nor other characters who perish from cocaine), but it is plausible that the victims suffered sudden cardiac death or a severe seizure. At Reggie de Veulle’s trial, a doctor testified that Billie Carleton had cocaine present in her nostrils and died as a result of an increase in blood pressure and the formation of blood clots in her heart due to the cocaine, which starved her body of oxygen and led to death. Interestingly, the doctor who attended Carleton the morning of her death stated he administered strychnine (and brandy) in an attempt to resuscitate the actress. She was 22 years old at the time of her death.

Rigor Mortis

Another intriguing scientific principle that features in The Affair at the Victory Ball is rigor mortis, the stiffening of muscles following death. Because Chris Davidson donned a harlequin costume and impersonated Lord Cronshaw within 10 minutes of his cohorts finding the body, a doctor testified that the stiffening of Cronshaw’s body was abnormal. However, because Cronshaw had been killed several hours prior, this was actually the natural process of rigor mortis. In addition to suggesting the time of death, it also led to the discovery of the important clue of the green pompon, which was clenched in Cronshaw’s fist.

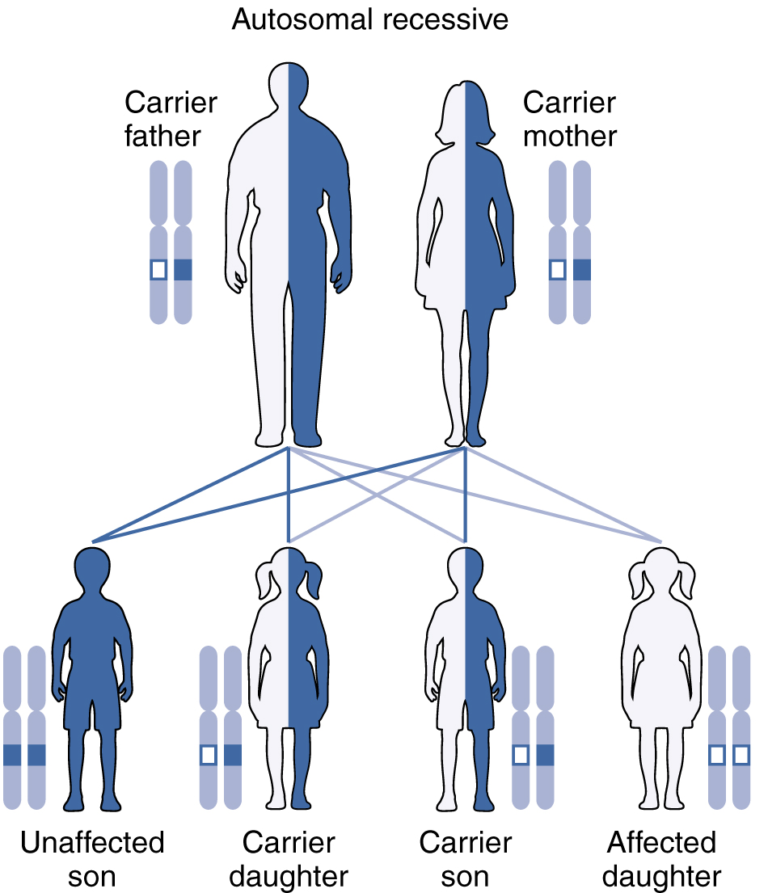

Immediately following death, all muscles in the body are fully relaxed. Within the first hour, some of the smaller muscle groups (such as the jaw and eyelids) begin to stiffen, followed by larger muscle groups. The timing of onset and development of rigor mortis can vary considerably due to factors such as the ambient temperature, and rigor mortis develops more quickly in higher temperatures.

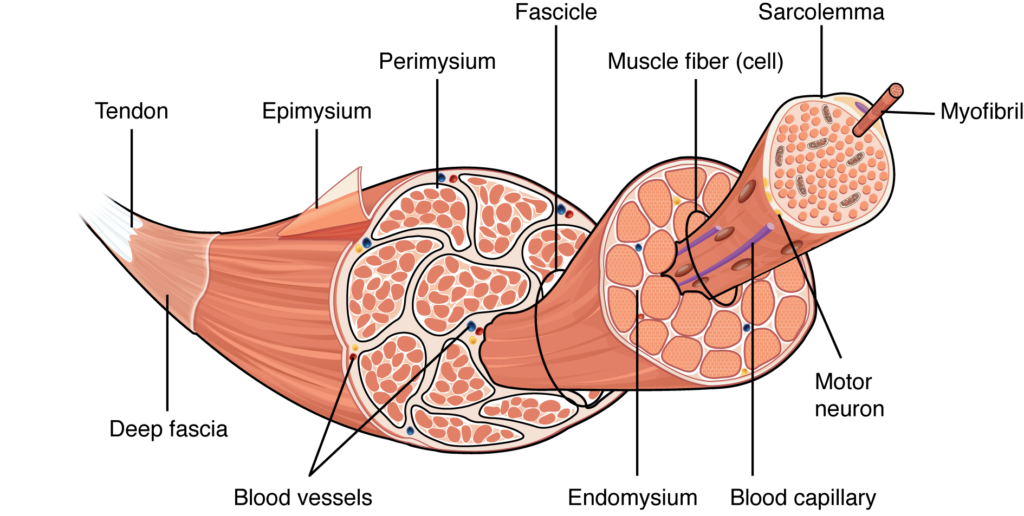

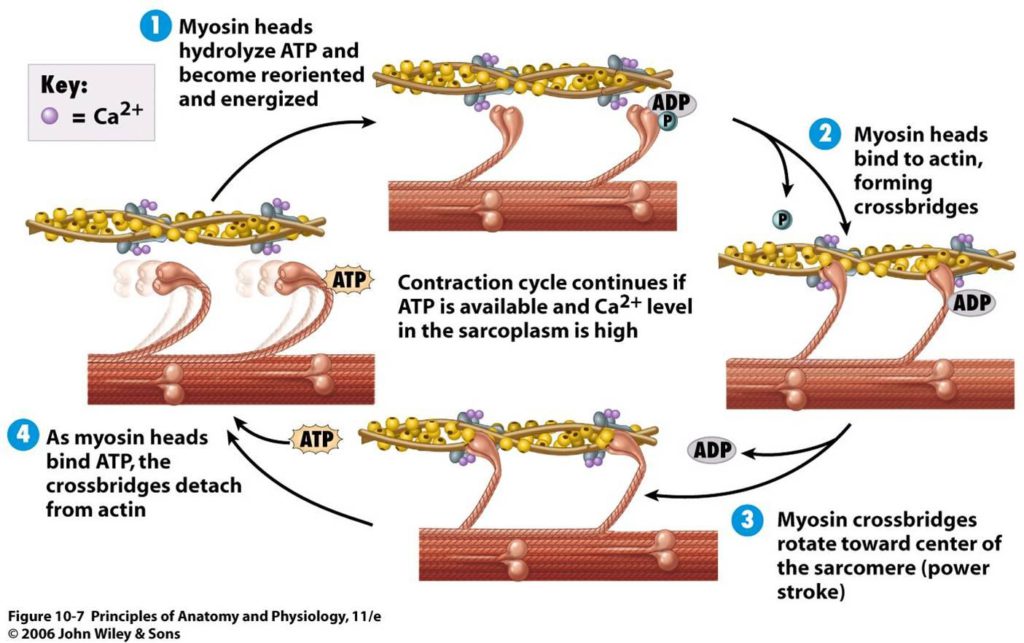

In a living body, the functional unit of skeletal muscles, myofibrils, comprise the myofilaments actin and myosin. To contract, they are acted upon by adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is an enzymatic cofactor that is involved in intracellular energy transfer. In the presence of ATP, actin and myosin form the compound actomyosin, which physically shortens during muscle contraction. Shortly after death, the production of ATP ceases, and the crossbridges formed between actin and myosin no longer break down. This results in the muscle stiffening and shortness that is characteristic of rigor mortis.

An enzyme is a protein that catalyzes chemical reactions by reducing the energy required, and they are not consumed by the reaction. An enzymatic cofactor is a molecule that binds to a specific region of an enzyme and is required for the normal function of the enzyme.

Rigor mortis may take 6 to 18 hours to fully take effect but can occur more quickly in higher temperatures. If the individual who dies was engaged in vigorous exercise, such as a struggle, before death, the onset may even be more rapid; this was likely the case with Lord Cronshaw as he attempted to fight off Chris Davidson.

The discovery of the green pompon clasped tightly in Cronshaw’s fist may be less scientifically plausible. A theory of “cadaveric spasm” posits that rigor mortis can instantly appear following death based on the appearance of dead bodies during World War I and World War II. However, there remains no credible biological explanation for such a phenomenon, and it is more likely that rigor mortis set in with the typical delay during the wars, but the bodies had continued to be affected by explosions on the battlefield until it fully set in.

Consequently, it is highly unlikely that Lord Cronshaw’s fist remained tightly clasped around the pompon from the time just before his death until his discovery. Because all muscles relax after death, he would have dropped the pompon, but as long as it remained just beneath the palm of his hand, he would have re-grasped it when rigor mortis took effect. This is possible but somewhat unrealistic given the short period of time between his death and the discovery of his body. Nevertheless, the inclusion of this plot point illustrates Christie’s basic understanding of rigor mortis.